Consider Lee's political strategies to impact the ratification process. How does he propose using political allies and connections, particularly in Virginia and Maryland, to resist the hasty adoption of the Constitution? In what ways does he aim to leverage public sentiment? What do these strategies reveal about the political dynamics of the time and the role of public opinion in the ratification process?

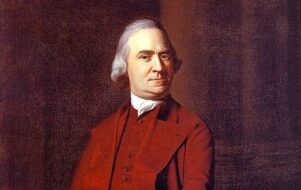

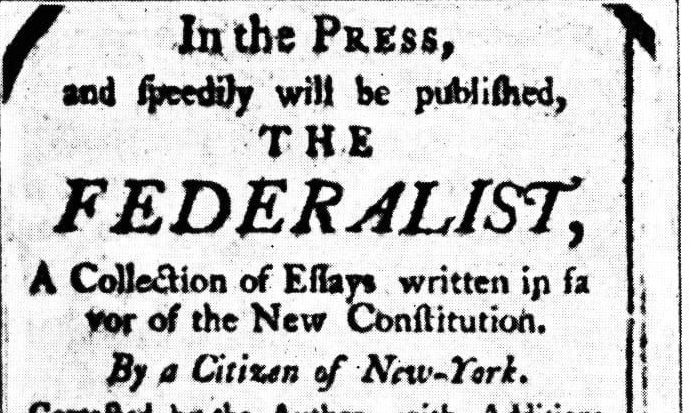

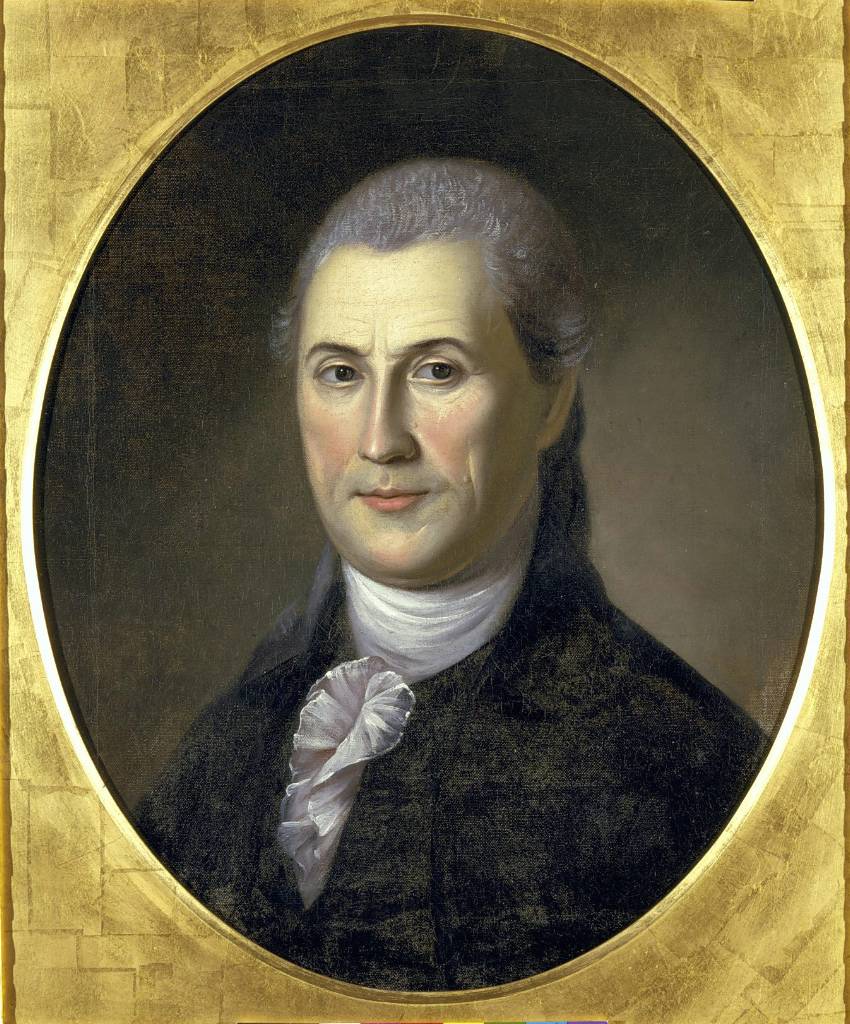

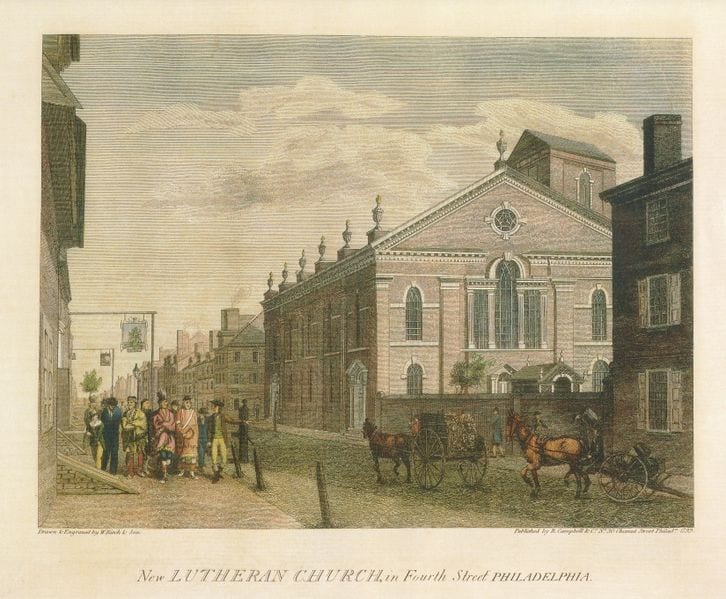

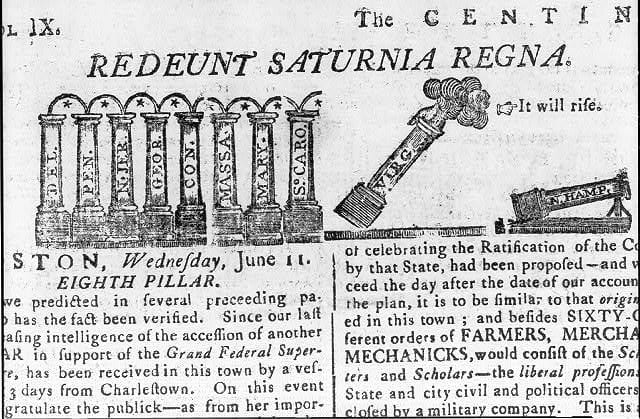

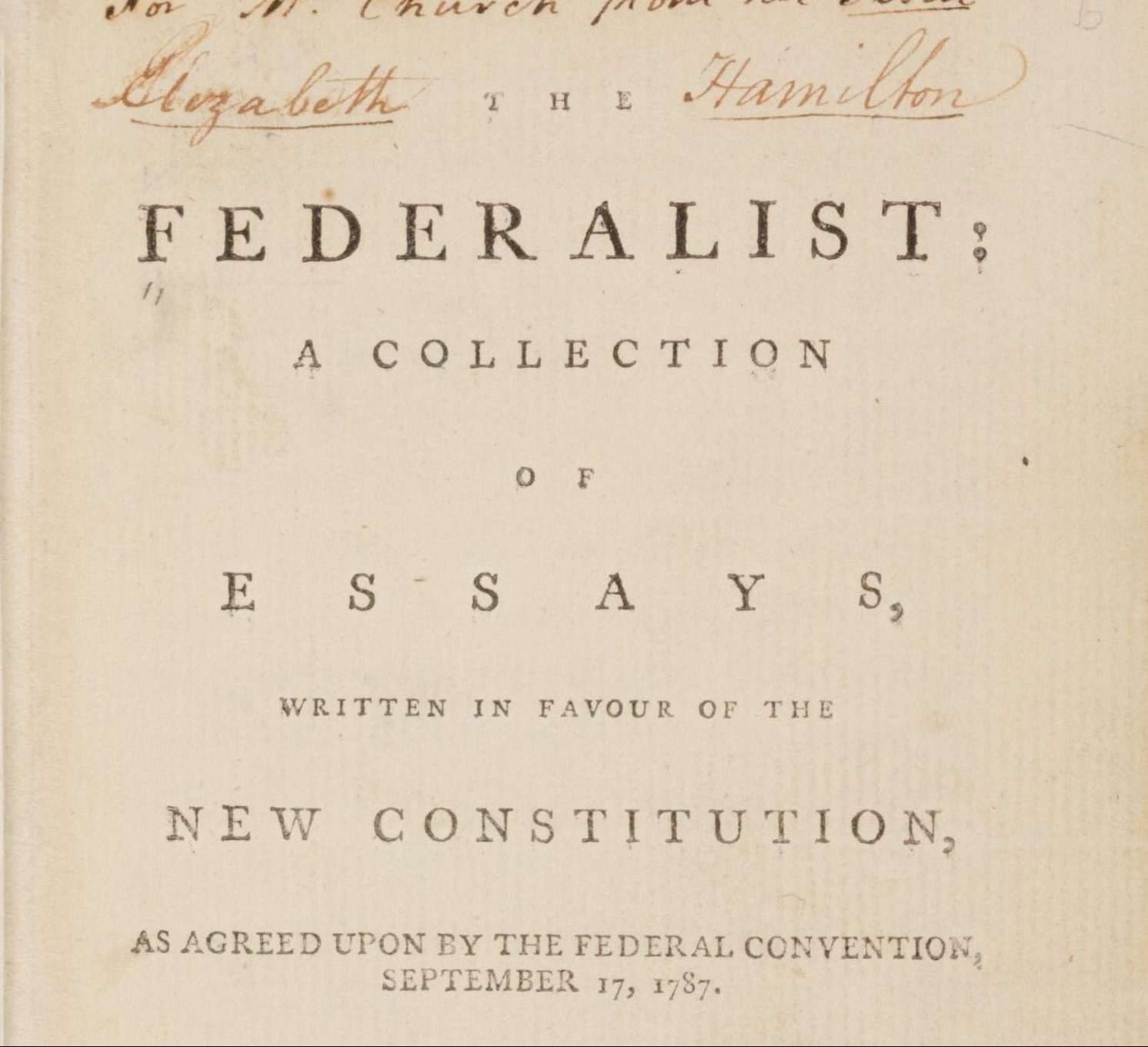

Given that Lee's letter and Centinel II, written by Pennsylvania statesman Samuel Bryan, were written just weeks apart in 1787, how do both documents reflect the rapidly evolving political climate of the ratification debate? In what ways do these documents highlight the growing tensions between Federalists and Antifederalists? How do their critiques reveal shared apprehensions about the Constitution's impact on individual rights and the need for a Bill of Rights?

Introduction

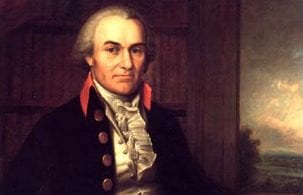

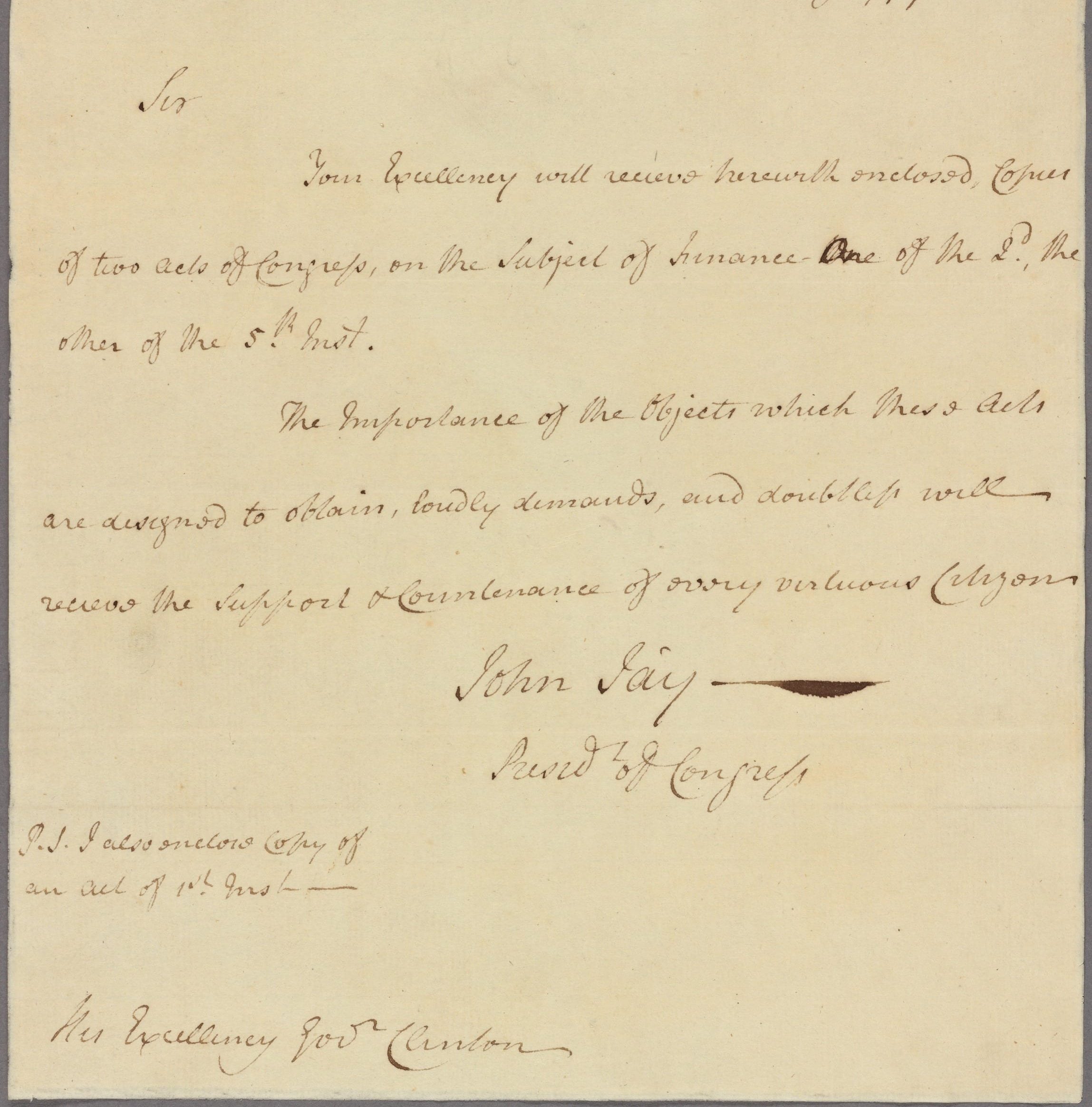

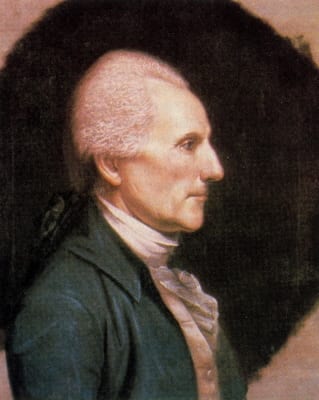

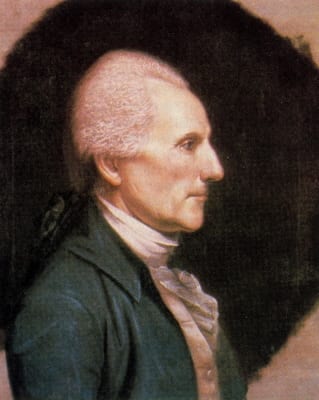

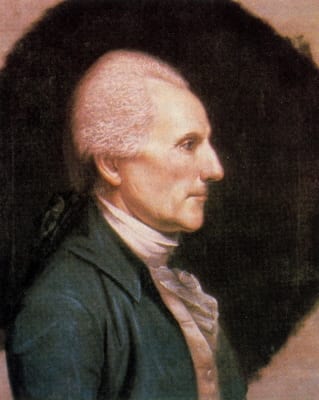

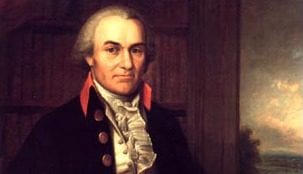

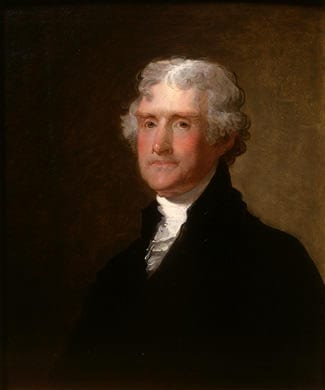

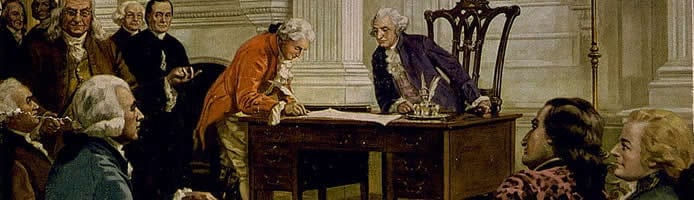

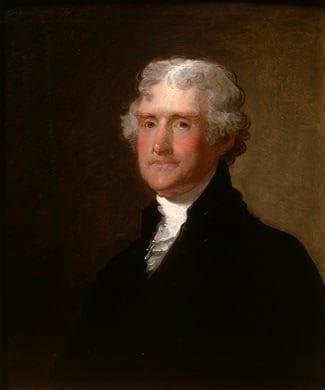

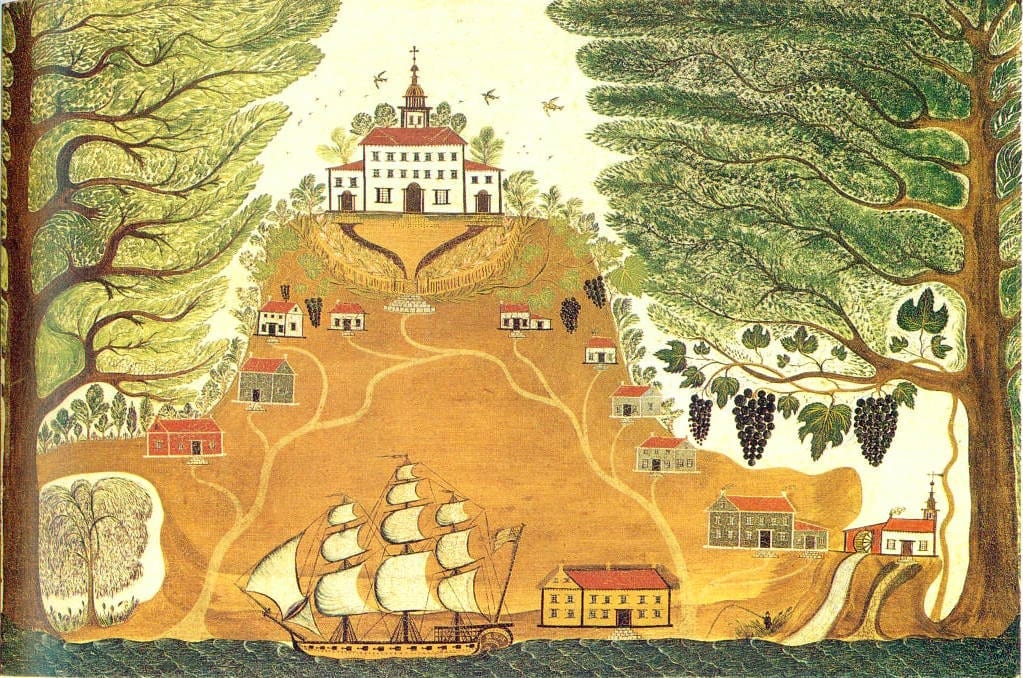

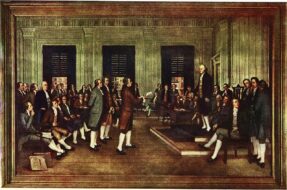

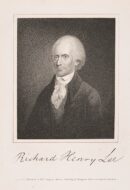

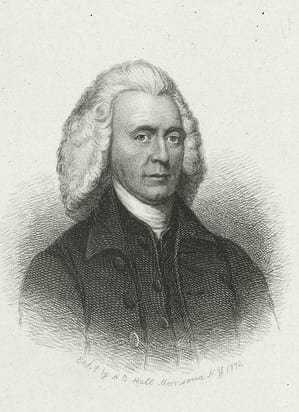

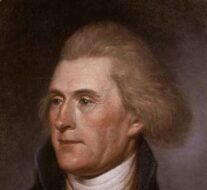

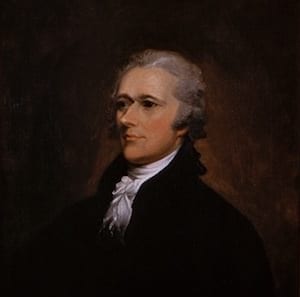

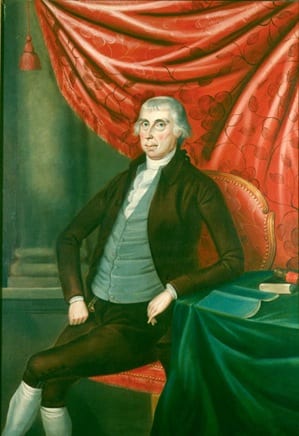

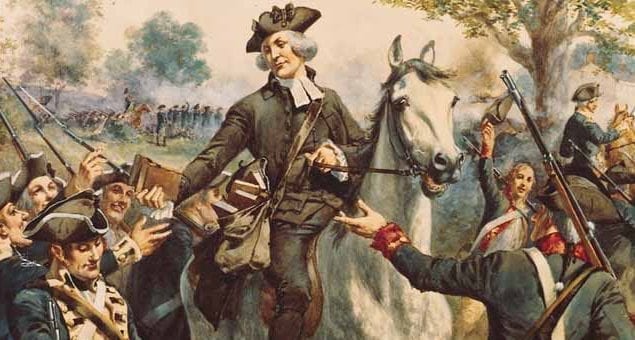

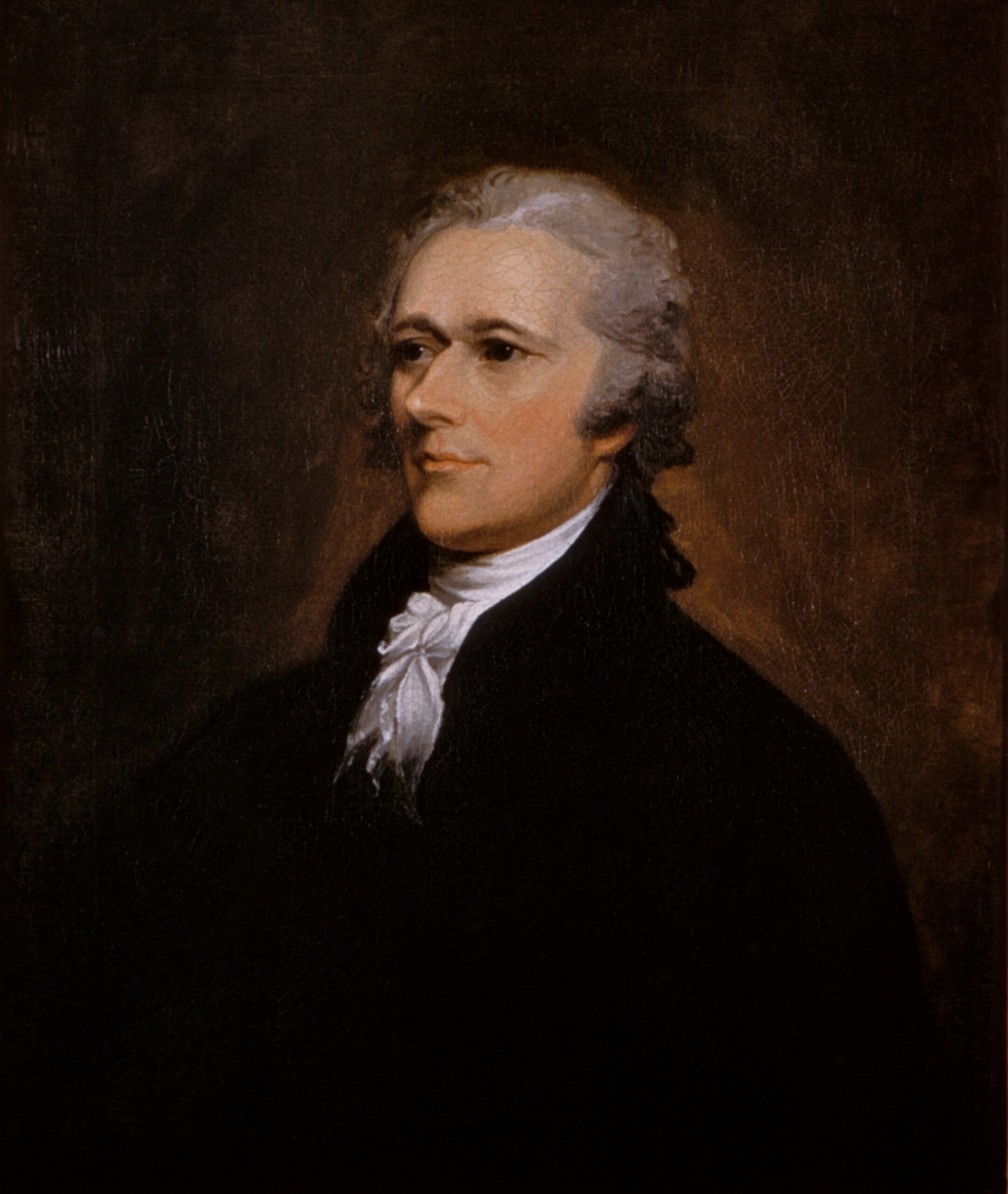

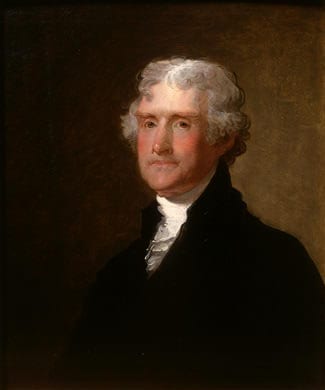

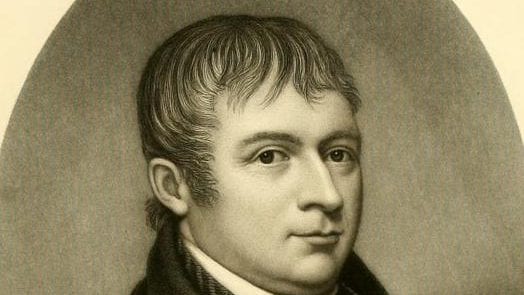

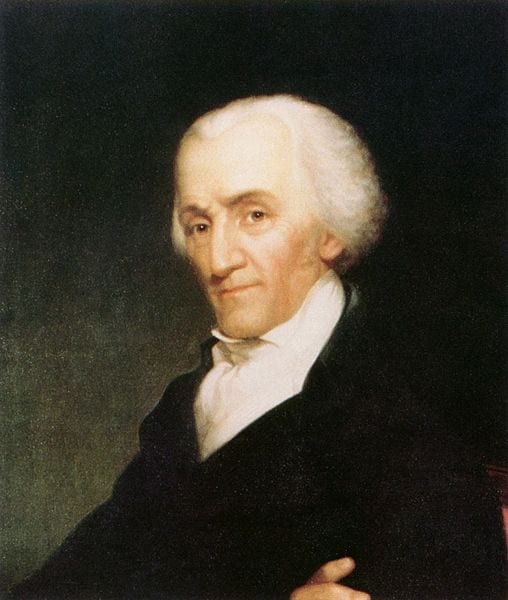

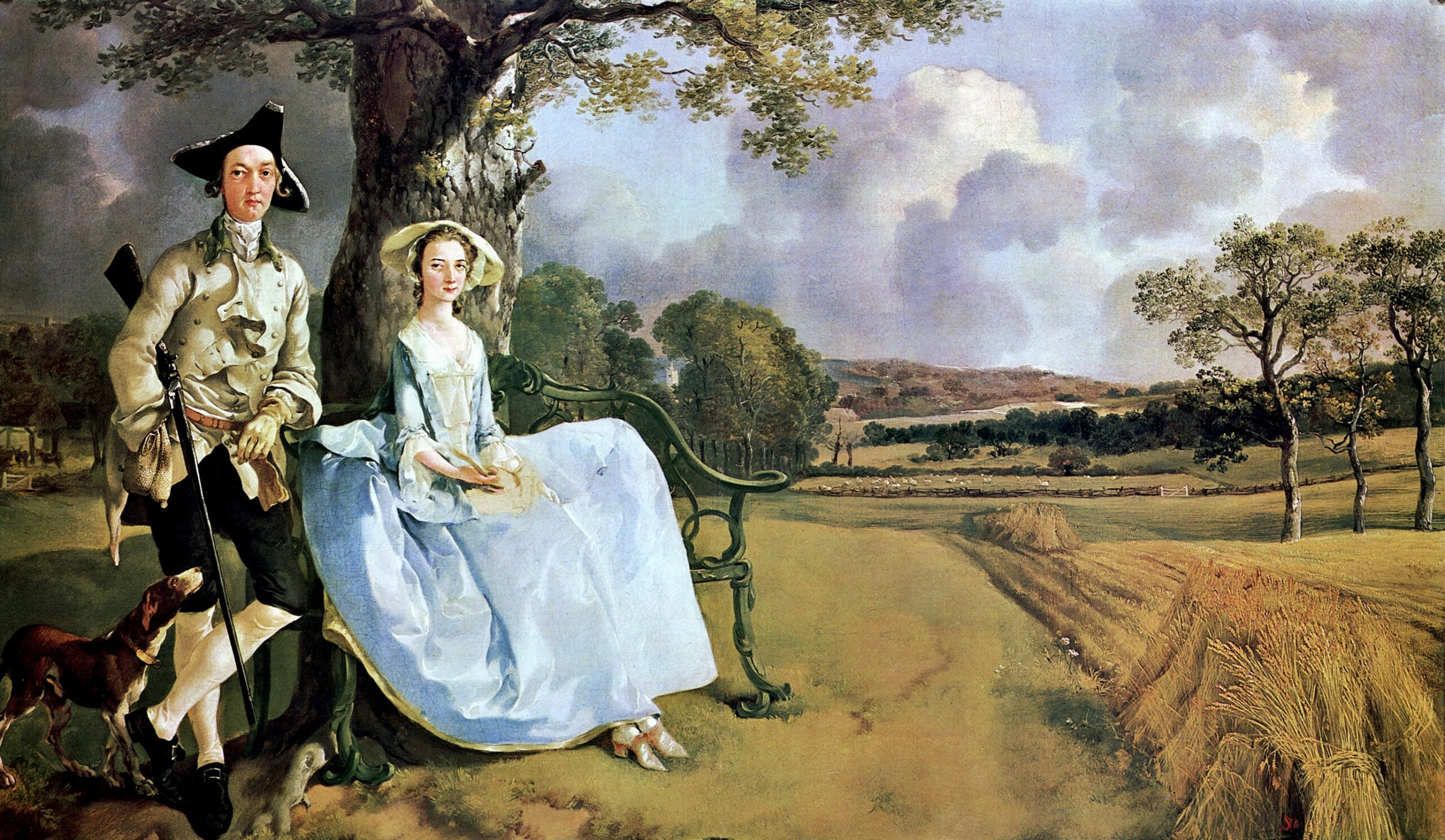

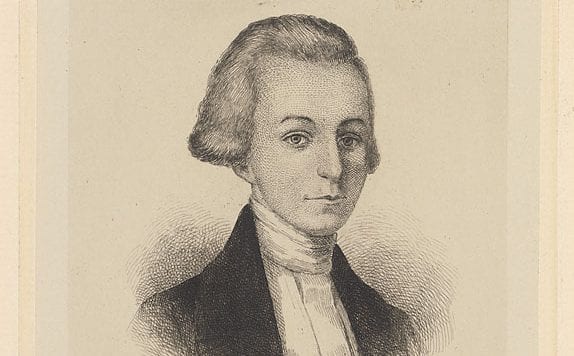

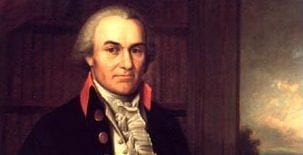

Richard Henry Lee (1732–1794) was a prominent Virginia statesman and delegate to the Continental Congress. During his time in Congress, Lee introduced three resolutions that shaped American history. The first, known as the “Lee Resolution,” called for independence from Britain and ultimately led to the Declaration of Independence. He also proposed resolutions to establish foreign alliances and draft a confederation plan. Lee did not attend the Constitutional Convention, but like fellow Virginian George Mason who did attend, he opposed ratifying the Constitution.

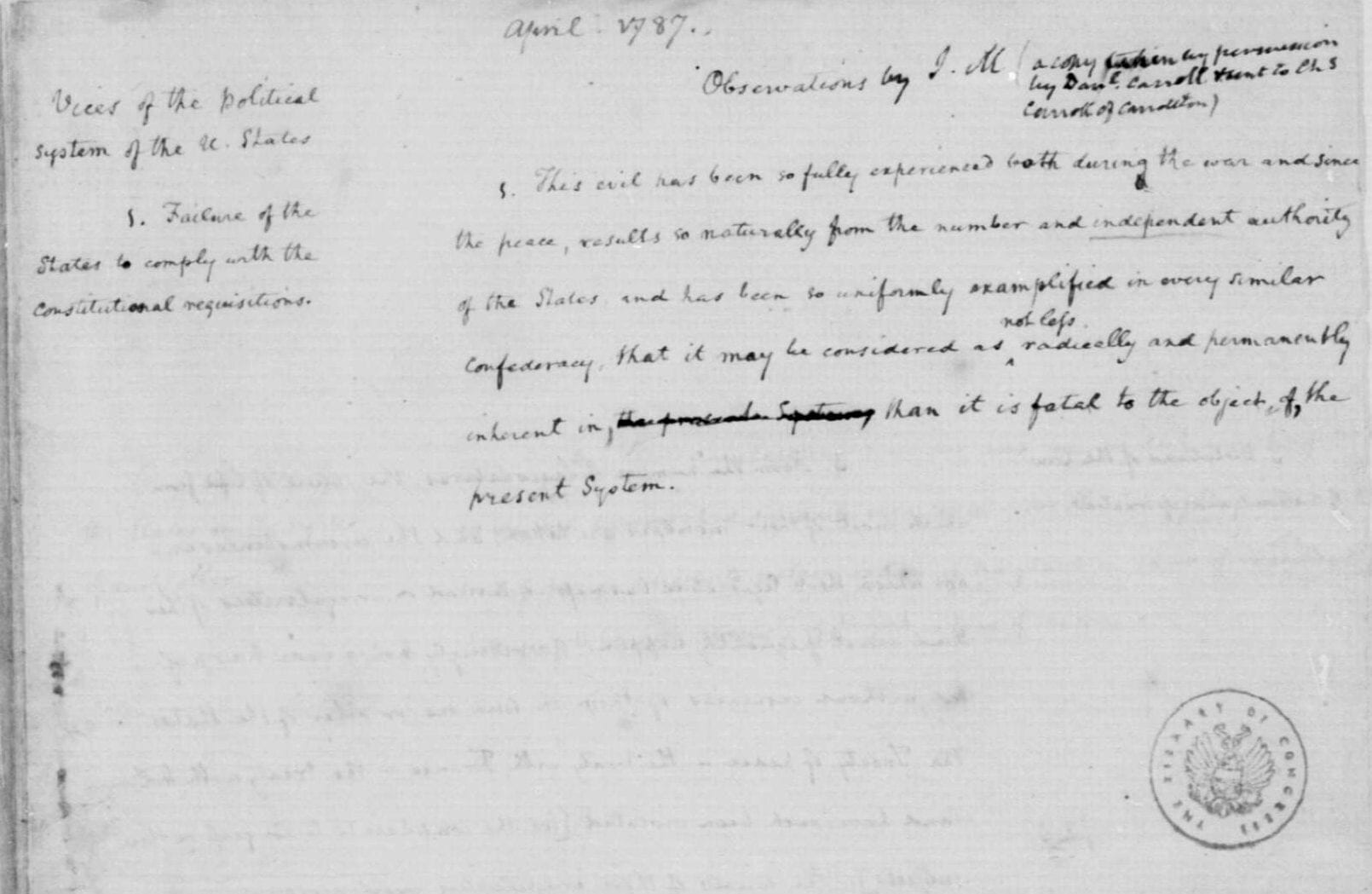

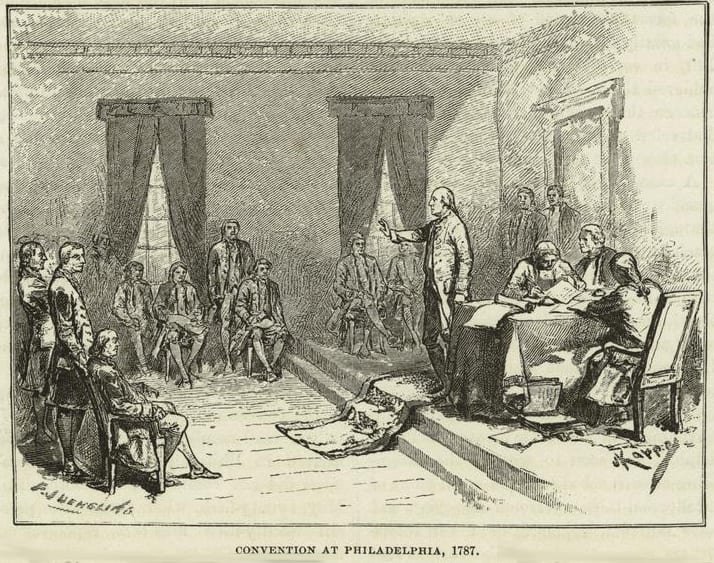

Lee wrote to Mason in October 1787, after the Constitutional Convention had concluded in September. Although Virginia’s ratifying Convention was not scheduled to convene until the following summer, Antifederalists like Lee and Mason were already critiquing the new Constitution and strategizing about political maneuvers to achieve their objectives. In his letter, Lee detailed his efforts to propose amendments to the Constitution; however, he encountered resistance from delegates who favored an expedited adoption of the document without modifications. A primary issue for Antifederalists was the omission of a declaration of rights, prompting Lee to recommend several strategies addressing this concern, including leveraging political contacts and advising the people of Virginia that ratification of the Constitution without amendments would endanger their civil liberties.

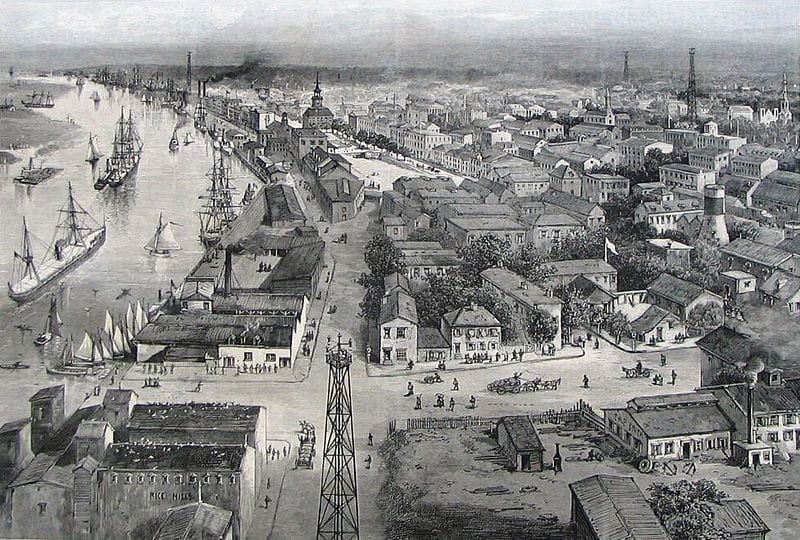

Furthermore, Lee expressed apprehension regarding the ratification process, asserting that the expedited timeline was a tactic utilized by Federalists to minimize debate and facilitate the process “with as little opposition as possible.” Lee also critiqued the Convention for exceeding its authority by establishing a new government. He believed this action was unjustified under Article 13 of the Articles of Confederation, which specified that any alterations to the government required unanimous consent. He argued that the proposed Constitution should not be adopted because it granted excessive power to the central government, undermining states’ rights. Lee expressed concern that this concentration of power could lead to tyranny as well as economic implications favoring the mercantile North at the expense of the agrarian South.

Lee’s concerns reflected broader reservations shared by Antifederalists regarding the potential deterioration of civil liberties and the need for specific protections against government overreach. These issues were central to the ratification debate and instrumental in gaining support for a Bill of Rights which ultimately convinced some remaining states to ratify the new Constitution.

Lee, Richard H. “To George Mason.” The Letters of Richard Henry Le, Volume II, edited by Curtis J. Ballagh, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1914. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uva.x000338030.

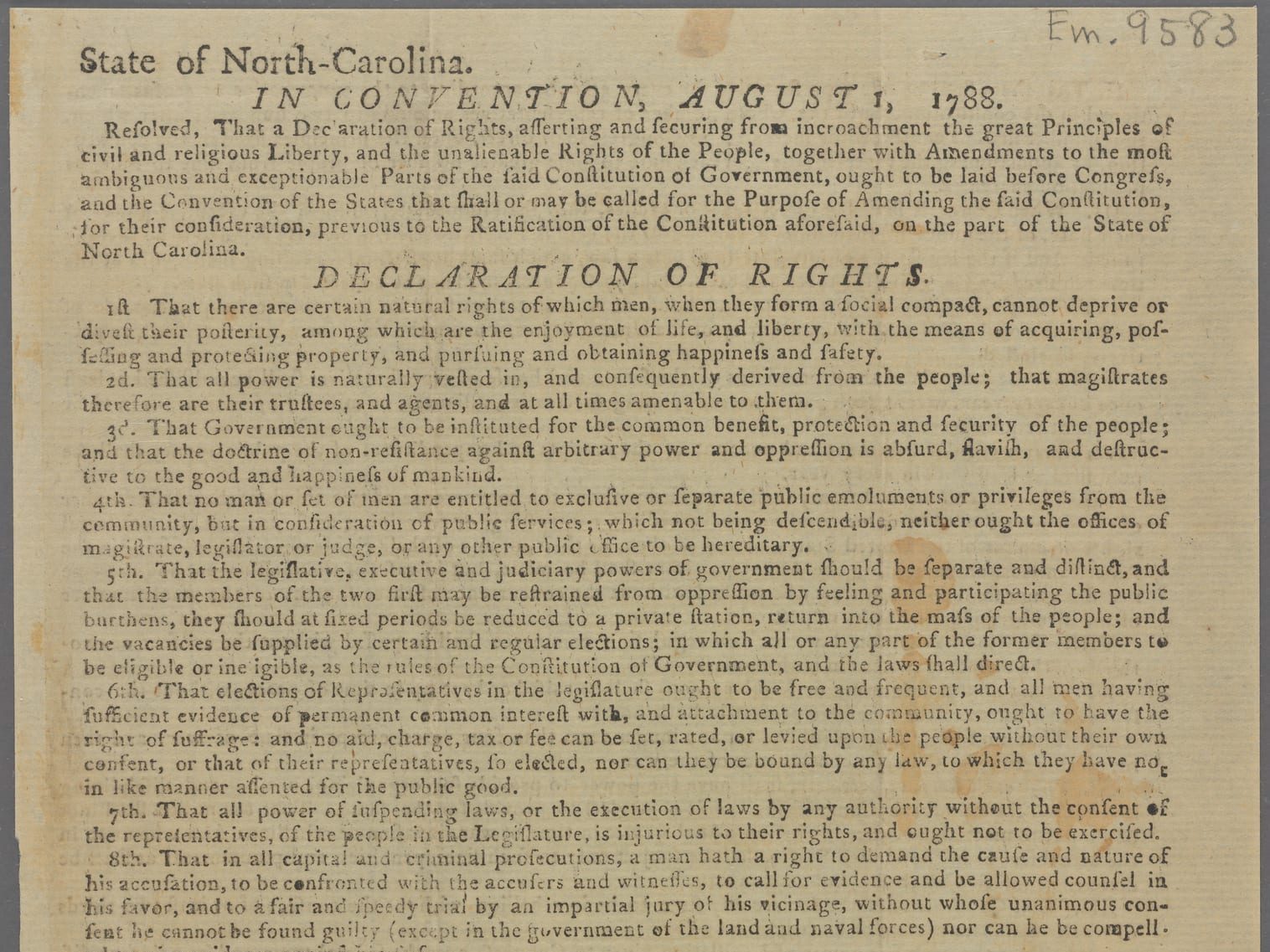

I have waited until now to answer your favor of September 10th from Philadelphia, that I might inform you how the Convention plan of government was entertained by Congress. Your prediction of what would happen in Congress was exactly verified. It was with us, as with you, this or nothing; and his urged with a most extreme intemperance. The greatness of the powers given, and the multitude of places to be created produce a coalition of monarchy men, military men, aristocrats and drones whose noise, impudence and zeal exceeds all belief. Whilst the commercial plunder of the South stimulates the rapacious trader. In this state of things the patriot voice is raised in vain for such changes and securities as reason and experience prove to be necessary against the encroachments of power upon the indispensable rights of human nature. Upon due consideration of the Constitution under which we now act, some of us were clearly of opinion that the Thirteenth Article of the Confederation precluded us from giving an opinion concerning a plan subversive of the present system, and eventually forming a new Confederacy of nine instead of thirteen States. The contrary doctrine was asserted with great violence in expectation of the strong majority with which they might send it forward under terms of much approbation. Having procured an opinion that Congress was qualified to consider, to amend, to approve or disapprove. The next game was to determine that though a right to amend existed, it would be highly inexpedient to exercise that right, but merely to transmit it with respectful marks of approbation. In this state of things I availed myself of the right to amend, and moved the amendments, a copy of which I send herewith, and called the ayes and nays to fix them on the journal. This greatly alarmed the majority & vexed them extremely; for the plan is to push the business on with great dispatch, and with as little opposition as possible, that it may be adopted before it has stood the test of reflection & due examination. They found it most eligible at last to transmit it merely, without approving or disapproving, provided nothing but the transmission should appear on the journal. This compromise was settled and they took the opportunity of inserting the word unanimously, which applied only to simple transmission, hoping to have it mistaken for an unanimous approbation of the thing. It states that Congress having received the Constitution unanimously transmit it &c. It is certain that no approbation was given. This Constitution has a great many excellent regulations in it, and if it could be reasonably amended would be a fine system. As it is, I think ’tis past doubt, that if it should be established, either a tyranny will result from it, or it will be prevented by a civil war. I am clearly of opinion with you that it should be sent back with amendments reasonable, and assent to it withheld until such amendments are admitted. You are well acquainted with Mr. Stone[1] and others of influence in Maryland. I think it will be a great point to get Maryland and Virginia to join in the plan of amendments and return it with them. If you are in correspondence with our chancellor Pendleton[2] it will be of much use to furnish him with the objections, and if he approves our plan, his opinion will have a great weight with our Convention; and I am told that his relation Judge Pendleton[3] of South Carolina has decided weight in that State, and that he is sensible and independent. How important will it be then to procure his union with our plan, which might probably be the case if our chancellor was to write largely and pressingly to him on the subject, that if possible it may be amended there also. It is certainly the most rash and violent proceeding in the world to cram thus suddenly into men a business of such infinite moment to the happiness of millions. One of your letters will go by the packet, and one by a merchant ship.

My compliments if you please, to your lady & to the young ladies & gentlemen. I am, dear sir, affectionately yours.

P.S. Suppose when the Assembly recommended a Convention to consider this new Constitution they were to use some words like these: it is earnestly recommended to the good people of Virginia to send their most wise and honest men to this Convention that it may undergo the most intense consideration before a plan shall be without amendments adopted that admits of abuses being practiced by which the best interests of this country may be injured, and civil liberty greatly endangered. This might perhaps give a decided tone to the business.

Please to send my son Ludwell[4] a copy of the amendments proposed by me to the new Constitution sent herewith.

- 1. Thomas Stone (1743–1787), elected as a delegate from Maryland but declined to serve at the Constitutional Convention.

- 2. Edmund Pendleton (1721–1803), served as president of Virginia’s ratifying convention in 1788.

- 3. Henry Pendleton (1750–1788), nephew of Edmund Pendleton, he served as a delegate to the South Carolina Ratifying Convention and voted in favor of the Constitution.

- 4. Ludwell Lee (1760–1836), Richard Henry Lee’s son who served as a lawyer in Virginia.

Caesar, Letter I

October 01, 1787

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

![Finley, A. (1829) Pennsylvania. Philada. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688548/.](/content/uploads/2024/02/Map-of-PA--273x190.jpg)