No related resources

Introduction

Between November 1860, when Abraham Lincoln was elected President, and March 4, 1861, when he took the oath of office, seven slave states formally seceded from the Union. One of his immediate goals as President was to halt that parade. However, four more states seceded after Lincoln responded to the Confederacy’s attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, calling for 75,000 volunteers to crush the rebellion. Virginia was the most significant of the final four seceding states. Its northern border sat just across the Potomac River from Washington, DC. To prevent the nation’s capital from being surrounded by enemy territory, Lincoln had to prevent Maryland, a slave state with southern sympathies, from joining the Confederacy. Lincoln moved quickly. Although Congress was not scheduled to convene until December 1861, he called for a special session starting July 4. On April 27, 1861, he suspended the writ of habeas corpus along the rail lines between Washington and Philadelphia, authorizing his military commanders to arrest and retain citizens they believed threatened public safety or military operations.

The writ of habeas corpus involves a legal process that originated in English common law. Habeas corpus is a Latin phrase meaning to “have the body.” Its purpose is to prevent persons from being arrested and detained without probable cause of committing a specific crime. If an illegal arrest is suspected, the jailed individual can seek a writ of habeas corpus, demanding that the arrested person appear before the court. A judge then rules whether the arrest is legal, or the person must be released. Under the Constitution, the writ of habeas corpus can be suspended in “Cases of Rebellion or Invasion, where the public Safety may require it.” Clearly, the Civil War constituted a case of rebellion. Yet the question arose, which branch of government can constitutionally suspend the writ, Congress or the Executive? The suspension clause is found in Section 9 of the Constitution’s Article 1, the article covering Congressional powers.

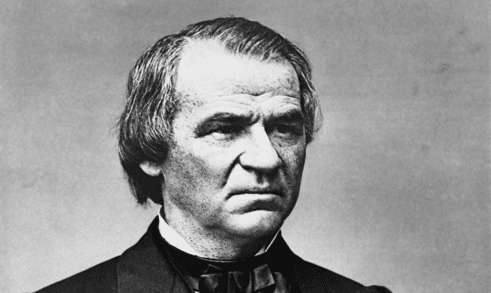

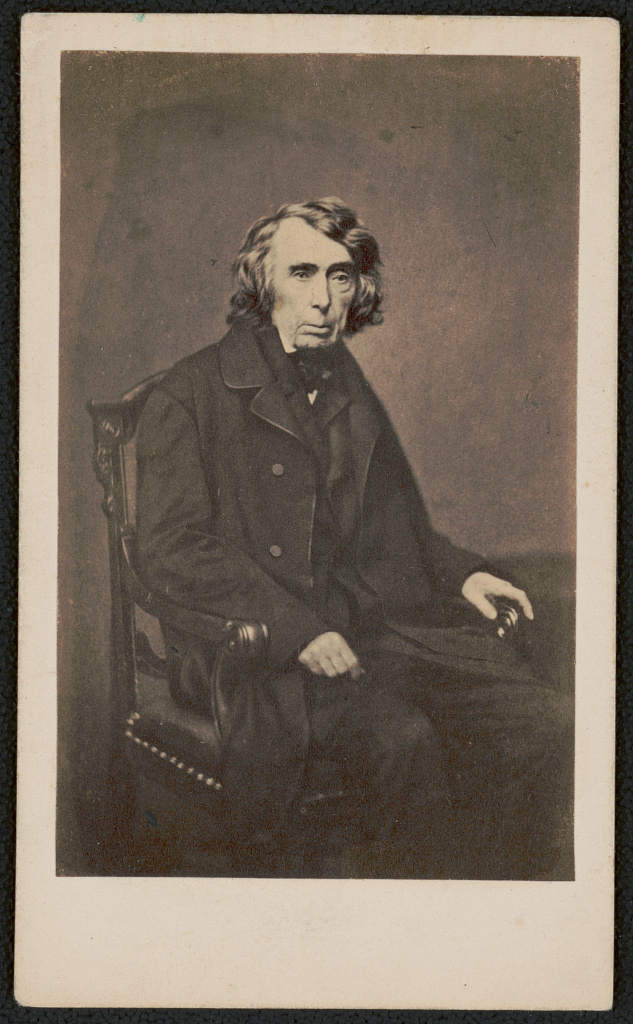

When John Merryman, a suspected southern sympathizer, was arrested without a warrant in Maryland on May 25, 1861, he sought relief from the US Circuit Court of Maryland, supervised by Chief Justice Roger Taney. Taney issued a writ of habeas corpus demanding that General George Cadwalader appear in his court with Merryman justifying the Marylander’s arrest. Cadwalader refused. He wrote the Chief Justice that he was authorized to suspend the writ by President Lincoln; therefore, the arrest was legally valid. When subsequent communication between Taney and Cadwalader failed to resolve the dispute, Taney issued an oral opinion on May 28, 1861, followed by a written opinion on June 1, 1861.

In his opinion, Taney argued that although the Constitution permits the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus during a rebellion or insurrection, it does so in a section of the Constitution that follows the enumerated Congressional powers listed in Section Eight and places specific restrictions on Congressional powers. Taney argued that the location of the habeas corpus clause gave the legislative branch, not the executive, the power to suspend the writ.

Source: Merryman, John, and Taney, Roger Brooke. The Merryman Habeas Corpus Case, Baltimore: The Proceedings in Full, and Opinion of Chief Justice Taney, 6-16. United States: J. L. Power, 1861. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Merryman_Habeas_Corpus_Case_Baltimor/Nl4wAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Ex parte John Merryman.

Before the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, at Chambers.

The application in this case for a writ of habeas corpus is made to me under the 14th section of the Judiciary Act of 1789, which renders effectual for the citizen the Constitutional privilege of the writ of habeas corpus. That act gives to the courts of the United States, as well as to each Justice of the Supreme Court, and to every District Judge, power to grant writs of habeas corpus for the purpose of an inquiry into the cause of commitment. The petition was presented to me at Washington under the impression that I would order the prisoner to be brought before me there, but as he was confined in fort McHenry, at the city of Baltimore, which is in my circuit, I resolved to hear it in the latter city, as obedience to the writ, under such circumstances, would not withdraw General Cadwallader, who had him in charge, from the limits of his military command.

The petition presents the following case: The petitioner resides in Maryland, in Baltimore county. While peaceably in his own house, with his family, it was, at two o’clock in the morning of the 25th of May, 1861, entered by an armed force, professing to act [under] military orders. He was then compelled to rise from his bed, taken into custody, and conveyed to Fort McHenry, where he is imprisoned by the commanding officer, without warrant from any lawful authority.

The commander of the fort, Gen. George Cadwallader, by whom he is detained in confinement, in his return to the writ, does not deny any of the facts alleged in the petition. He states that the prisoner was arrested by order of Gen. Keim, of Pennsylvania, and conducted as a prisoner to Fort McHenry by his order, and placed in his, (Gen. Cadwallader’s) custody, to be there detained by him as a prisoner.

A copy of the warrant, or order, under which the prisoner was arrested, was demanded by his counsel, and refused. And it is not alleged in the return that any specific act constituting an offence [sic] against the laws of the United States, has been charged against him upon oath, but he appears to have been arrested upon general charges of treason and rebellion, without proof, and without giving the names of the witnesses, or specifying the acts, which in the judgment of the military officer, constituted these crimes. And having the prisoner thus in custody upon these vague and unsupported accusations, he refuses to obey the writ of habeas corpus, upon the ground that he is duly authorized by the President to suspend it.

The case, then, is simply this. A military officer, residing in Pennsylvania, issues an order to arrest a citizen of Maryland upon vague and indefinite charges, without any proof, so far as appears. Under this order his house is entered in the night; he is seized as a prisoner and conveyed to Fort McHenry, and there kept in close confinement. And when a habeas corpus is served on the commanding officer, requiring him to produce the prisoner before a Justice of the Supreme Court, in order that he may examine into the legality of the imprisonment, the answer of the officer is, that he is authorized by the President to suspend the writ of habeas corpus at his discretion, and, in the exercise of that discretion, suspends it in this case, and on that ground refuses obedience to the writ.

As the case comes before me, therefore, I understand that the President not only claims the right to suspend the writ of habeas corpus himself at his discretion, but to delegate that discretionary power to a military officer, and to leave it to him to determine whether he will or will not obey judicial process that may be served upon him.

No official notice has been given to the courts of justice or to the public, by proclamation or otherwise, that the President claimed this power and had exercised it in the manner stated in the return. And I certainly listened to it with some surprise, for I had supposed it to be one of those points of constitutional law, upon which there was no difference of opinion, and that it was admitted on all hands that the privilege of the writ could not be suspended except by act of Congress.

When the conspiracy of which Aaron Burr was the head became so formidable, and was so extensively ramified, as to justify, in Mr. Jefferson’s opinion, the suspension of the writ, he claimed, on his part, no power to suspend it, but communicated his opinion to Congress, with all the proofs in his possession, in order that Congress might exercise its discretion upon the subject, and determine whether the public safety required it. And in the debate which took place upon the subject, no one suggested that Mr. Jefferson might exercise the power himself, if, in his opinion, the public safety demanded it.

Having, therefore regarded the question as too plain and too well settled to be open to dispute, if the commanding officer had stated that upon his own responsibility, and in the exercise of his own discretion, he refused obedience to the writ, I should have contented myself with referring to the clause in the Constitution, and to the construction it received from every jurist and statesman of that day, when the case of Burr was before them. But being thus officially notified that the privilege of the writ has been suspended under the orders and by the authority of the President, and, believing, as I do, that the President has exercised a power which he does not possess under the Constitution, a proper respect for the high office he fills, requires me to state plainly and fully the grounds of my opinion, in order to show that I have not ventured to question the legality of this act without a careful and deliberate examination of the whole subject.

The clause in the Constitution, which authorizes the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, is in the 9th section of the first article.

This article is devoted to the Legislative Department of the United States, and has not the slightest reference to the Executive department. It begins by providing "that all legislative powers therein granted, shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives." And after prescribing the manner in which these two branches of the legislative department shall be chosen, it proceeds to enumerate specifically the legislative powers which it thereby grants, and legislative powers which it expressly prohibits, and, at the conclusion of this specification, a clause is inserted, giving Congress "the power to make all laws which may be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers, and all other powers vested by this Constitution in the government of the United States or in any department or office thereof."

The power of legislation granted by this latter clause is by its words carefully confined to the specific objects before enumerated.—But as this limitation was unavoidably somewhat indefinite, it was deemed necessary to guard more effectually certain great cardinal principles essential to the liberty of the citizen, and to the rights and equality of the States, by denying to Congress in express terms, any power of legislating over them. It was apprehended, it seems, that such legislation might be attempted under the pretext that it was necessary and proper to carry into execution the powers granted; and it was determined that there should be no room to doubt, where rights of such vital importance were concerned, and accordingly, this clause is immediately followed by an enumeration of certain subjects, to which the powers of legislation shall not extend; and the great importance which the framers of the Constitution attached to the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus to protect the liberty of the citizen, is proved by the fact that its suspension, except in cases of invasion and rebellion, is first in the list of prohibited powers—and even in these cases, the power is denied, and its exercise prohibited, unless the public safety shall require it. It is true, that in the cases mentioned, Congress is of necessity the judge of whether the public safety does or does not require it; and its judgment is conclusive. But the introduction of these words is a standing admonition to the legislative body of the danger of suspending it, and of the extreme caution they should exercise before they give the Government of the United States such power over the liberty of a citizen.

It is the 2d article of the Constitution that provides for the organization of the Executive Department, and enumerates the powers conferred on it, and prescribes its duties. And if the high power over the liberty of the citizen now claimed, was intended to be conferred on the President, it would undoubtedly be found in plain words in this article. But there is not a word in it that can furnish the slightest ground to justify the exercise of this power.

The article begins by declaring that the Executive power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America, to hold his office during the term of four years—and then proceeds to prescribe the mode of election, and to specify, in precise and plain words, the powers delegated to him and the duties imposed upon him. And the short term for which he is elected, and the narrow limits to which his power is confined, show the jealousy and apprehensions of future danger which the framers of the Constitution felt in relation to that department of the Government—and how carefully they withheld from it many of the powers belonging to the Executive branch of the English Government, which were considered as dangerous to the liberty of the subject—and conferred (and that in clear and specific terms) those powers only which were deemed essential to secure the successful operation of the Government.

He is elected, as I have already said, for the brief term of four years, and is made personally responsible, by impeachment, for malfeasance in office. He is from necessity and the nature of his duties, the commander-in-chief of the army and navy, and of the militia, when called into actual service. But no appropriation for the support of the army can be made by Congress for a longer term than two years, so that it is in the power of the succeeding House of Representatives to withhold the appropriation for its support, and thus disband it, if, in their judgment, the President used, or designed to use it for improper purposes. And although the militia, when in actual service, are under his command, yet the appointment of the officers is reserved to the States, as a security against the use of the military power for purposes dangerous to the liberties of the people or the rights of the States.

So, too, his powers in relation to the civil duties and authority necessarily conferred on him, are carefully restricted, as well as those belonging to his military character. He cannot appoint the ordinary officers of Government nor make a treaty with a foreign nation or Indian tribe without the advice and consent of the Senate, and cannot appoint even inferior officers unless he is authorized by an act of Congress to do so. He is not empowered to arrest any one charged with an offence against the United States, and whom he may, from the evidence before him, believe to be guilty—nor can he authorize any officer, civil or military, to exercise this power; for the 5th article of the amendments to the Constitution expressly provides that no person "shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law."—that is, judicial process. And even if the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus was suspended by act of Congress, and a party not subject to the rules and articles of war was afterwards arrested and imprisoned by regular judicial process, he could not be detained in prison or brought to trial before a military tribunal, for the article in the amendments to the Constitution, immediately following the one above referred to—that is, the 6th article—provides that "in all criminal prosecutions the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defence [sic]."

And the only power, therefore, which the President possesses, where the "life, liberty or property" of a private citizen is concerned, is the power and duty prescribed in the third section of the 2d article, which requires "that he shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed." He is not authorized to execute them himself, or through agents or officers, civil or military, appointed by himself, but he is to take care that they be faithfully carried into execution as they are expounded and adjudged by the co-ordinate branch of the Government, to which that duty is assigned by the Constitution. It is thus made his duty to come in aid of the judicial authority, if it shall be resisted by a force too strong to be overcome without the assistance of the Executive arm. But in exercising this power, he acts in subordinate to judicial authority, assisting it to execute its process and enforce its judgments.

With such provisions in the Constitution, expressed in language too clear to be misunderstood by any one, I can see no ground whatever for supposing that the President, in any emergency or in any state of things, can authorize the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, or arrest a citizen, except in aid of the judicial power. He certainly does not faithfully execute the laws if he takes upon himself legislative power by suspending the writ of habeas corpus—and the judicial power, also, by arresting and imprisoning a person without due process of law. Nor can any argument be drawn from the nature of sovereignty, or the necessities of government for [self-defense] in times of tumult and danger. The Government of the United States is one of delegated and limited powers. It derives it existence and authority altogether from the Constitution, and neither of its branches, Executive, Legislative or Judicial, can exercise any of the powers of government beyond those specified and granted. For the 10th article of the amendments to the Constitution, in express terms, provides that "the powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people."

Indeed, the security against imprisonment by executive authority, provided for in the fifth article of the amendments to the Constitution, which I have before quoted, is nothing more than a copy of a like provision in the English constitution, which had been firmly established before the Declaration of Independence.

Blackstone, in his Commentaries, (1st vol., 137) states it in the following words:

"To make imprisonment lawful, it must be either by process from the Courts of Judicature or by warrant from some legal officer having authority to commit to prison." And the people of the United Colonies, who had themselves lived under its protection while they were British subjects, were well aware of the necessity of this safeguard for their personal liberty. And no one can believe that in framing a government intended to guard still more efficiently the rights and liberties of the citizens against executive encroachment and oppression, they would have conferred on the President a power which the history of England had proved to be dangerous and oppressive in the hands of the Crown, and which the people of England had compelled it to surrender after a long and obstinate struggle on the part of the English Executive to usurp and retain it.

The right of the subject to the benefit of the writ of habeas corpus, it must be recollected, was one of the great points in controversy in England between arbitrary government and free institutions, and must, therefore, have strongly attracted the attention of statesmen engaged in framing a new, and, as they supposed, a freer government than the one which they had thrown off by the revolution. For, from the earliest history of the Common Law, if the person was imprisoned—no matter by what authority—he had a right to the writ of habeas corpus to bring his case before the King’s Bench; and if no specific offence was charged against him in the warrant of commitment, he was entitled to be forthwith discharged; and if an offence was charged which was bailable in its character, the court was bound to set him at liberty on bail. And the most exciting contests between the Crown and the people of England from the time of the Magna Charta, were in relation to the privilege of this writ, and they continued until the passage of the statute of 31st Charles 2d, commonly known as the great habeas corpus act. This statute put an end to the struggle, and finally and firmly secured the liberty of the subject from the usurpation and oppression of the executive branch of the Government. It nevertheless conferred no right upon the subject, but only secured a right already existing. For, although the right could not justly be denied, there was often no effectual remedy against its violation. Until the statute of the 13th William 3d, the Judges held their offices at the pleasure of the King, and the influence which he exercised over timid, time-serving and partizan [sic] Judges often induced them, upon some pretext or other to refuse to discharge the party, although he was entitled to it by law, or delayed their decisions from time to time, so as to prolong the imprisonment of persons who were obnoxious to the King for their political opinions, or had incurred his resentment in any other way.

The great and inestimable value of the habeas corpus act of the 31st Charles 2, is that it contains provisions which compel courts and judges, and all parties concerned, to perform their duties promptly, in the manner specified in the statute.

A passage in Blackstone’s Commentaries, showing the ancient state of the law upon this subject, and the abuses which were practiced through the power and influence of the Crown, and a short extract from Hallam’s Constitutional History, stating the circumstances which gave rise to the passage of this statute, explain briefly, but fully, all that is material to this subject.

Blackstone, in his Commentaries on the Laws of England, 3d vol., 133-134, says:

"To assert an absolute exemption from imprisonment in all cases, is inconsistent with every idea of law and political society, and in the end would destroy all civil liberty, by rendering its protection impossible.

"But the glory of the English law consists in clearly defining the times, the causes, and the extent, when, wherefore, and to what degree the imprisonment of the subject may be lawful. This it is which induces the absolute necessity of expressing upon every commitment the reason for which it is made, that the court upon a habeas corpus may examine into its validity, and according to the circumstances of the case, may discharge, admit to bail, or remand the prisoner.

"And yet early in the reign of Charles I., the Court of King’s Bench, relying on some arbitrary precedents (and those perhaps misunderstood,) determined that they would not, upon a habeas corpus, either bail or deliver a prisoner, though committed without any cause assigned, in case he was committed by the special command of the King or by the Lords of the Privy Council. This drew on a Parliamentary inquiry, and produced the Petition of Rights—3 Chas. I—which recites this illegal judgment and enacts that no freeman hereafter shall be so imprisoned or detained. But when in the following year Mr. Selden and others were committed by the Lords of the Council in pursuance of his Majesty’s special command, under a general charge of ’notable contempts, and stirring up sedition against the King and the Government,’ the judges delayed for two terms (including also the long vacation,) to deliver an opinion how far such a charge was bailable. And when at length they agreed that it was, they annexed a condition of finding sureties for their good behavior, which still protracted their imprisonment, the Chief Justice, Sir Nicholas Hyde, at the same time declaring that ’if they were again remanded for that cause perhaps the court would not grant a habeas corpus, being already acquainted with the cause of the imprisonment.’ But this was heard with indignation and astonishment by every lawyer present, according to Mr. Selden’s own account of the matter, whose resentment was not cooled at the distance of four-and-twenty years."

It is worthy of remark that the offences [sic] charged against the prisoner in this case, and relied on as a justification for his arrest and imprisonment, in their nature and character, and in the loose and vague manner in which they are stated, bear a striking resemblance to those assigned in the warrant for the arrest of Mr. Selden. And yet, even at that day, the warrant was regarded as such a flagrant violation of the rights of the subject, that the delay of the time-serving judges to set him at liberty upon the habeas corpus issued in his behalf, excited the universal indignation of the bar. The extract from Hallam’s Constitutional History is equally impressive and equally in point. It is in vol. 4, p. 14:

"It is a very common mistake, and not only among foreigners, but many from whom some knowledge of our constitutional laws might be expected, to suppose that this statute of Charles II. enlarged in a great degree our liberties, and forms a sort of epoch in their history. But though a very beneficial enactment, and eminently remedial in many cases of illegal imprisonment, it introduced no new principle, nor conferred any right upon the subject. From the earliest records of the English law, no freeman could be detained in prison, except upon a criminal charge, or conviction, or for a civil debt. In the former case it was always in his power to demand of the Court of King’s Bench a writ of habeas corpus ad subjiciendum directed to the person detaining him in custody, by which he was enjoined to bring up the body of the prisoner with the warrant of commitment, that the court might judge of its sufficiency, and remand the party, admit him to bail, or discharge him according to the nature of the charge. This writ issued of right, and could not be refused by the court. It was not to bestow an immunity from arbitrary imprisonment, which is abundantly provided for in Magna Charta, (if indeed it were not more ancient,) that the statute of Charles II. was enacted, but to cut off the abuses by which the government’s lust of power, and servile subtlety of Crown lawyers had impaired so fundamental a privilege."

While the value set upon this writ in England has been so great that the removal of the abuses which embarrassed its enjoyment have been looked upon as almost a new grant of liberty to the subject, it is not to be wondered that the continuance of the writ thus made effective should have been the object of the most jealous care. Accordingly, no power in England short of that of Parliament can suspend or authorize the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus. I quote again from Blackstone (1 Comm. 136): "But the happiness of our Constitution is, that it is not left to the executive power to determine when the danger of the state is so great as to render this measure inexpedient. It is the Parliament only, or legislative power, that whenever it sees proper, can authorize the Crown by suspending the habeas corpus for a short and limited time, to imprison suspected persons without giving any reason for so doing." And if the President of the United States may suspend the writ, then the Constitution of the United States has conferred upon him more regal and absolute power over the liberty of the citizen than the people of England have thought it safe to entrust to the Crown—a power which the Queen of England cannot exercise at this day, and which could not have been lawfully exercised by the Sovereign even in the reign of Charles the First.

But I am not left to form my judgment upon this great question, from analogies between the English Government and our own, or the commentaries of English jurists, or the decisions of English courts, although upon this subject they are entitled to the highest respect, and are justly regarded and received as authoritative by our Courts of Justice. To guide me to a right conclusion, I have the commentaries on the Constitution of the United States of the late Mr. Justice Story, not only one of the most eminent jurists of the age, but for a long time one of the brightest ornaments of the Supreme Court of the United States, and also the clear and authoritative decision of that Court itself, given more than half a century since, and conclusively establishing the principles I have above stated.

Mr. Justice Story, speaking in his Commentaries of the habeas corpus clause in the Constitution, says:

"It is obvious that cases of a peculiar emergency may arise which may justify, nay, even require, the temporary suspension of any right to the writ. But as it has frequently happened in foreign countries, and even in England, that the writ has, upon various pretexts and occasions, been suspended, whereby persons apprehended upon suspicion have suffered a long imprisonment, sometimes from design and sometimes because they were forgotten, the right to suspend it is expressly confined to cases of rebellion or invasion, where the public safety may require it. A very just and wholesome restraint, which cuts down at a blow a fruitful means of oppression, capable of being used in bad times to the worst of purposes. Hitherto no suspension of the writ has ever been authorized by Congress since the establishment of the Constitution. It would seem, as the power is given to Congress to suspend the writ of habeas corpus in cases of rebellion or invasion, that the right to judge whether the exigency had arisen must exclusively belong to that body." 3 Story’s Com. on the Constitution, section [1336].

And Chief Justice Marshall, in delivering the opinion of the Supreme Court, in the case of ex parte Bollman and Swartwout, uses this decisive language in 4 Cranch, 95:

"It may be worthy of remark, that this act (speaking of the one under which I am proceeding) was passed by the first Congress of the United States, sitting under a Constitution which had declared ’that the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus should not be suspended, unless, when in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety might require it.’ Acting under the immediate influence of this injunction, they must have felt, with peculiar force, the obligation of providing efficient means by which this great constitutional privilege should receive life and activity; for if the means be not in existence, the privilege itself would be lost, although no law for its suspension should be enacted. Under the impression of this obligation they give to all the courts the power of awarding writs of habeas corpus."

And again, in page 101:

"If at any time the public safety should require the suspension of the powers vested by this act in the courts of the United States, it is for the Legislature to say so. That question depends on political considerations, on which the Legislature is to decide. Until the Legislative will be expressed, this court can only see its duty, and must obey the laws."

I can add nothing to these clear and emphatic words of my great predecessor.

But the documents before me show that the military authority in this case has gone far beyond the mere suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus. It has, by force of arms, thrust aside the judicial authorities and officers to whom the Constitution has confided the power and duty of interpreting and administering the laws, and substituted a military government in its place, to be administered and executed by military officers. For, at the time these proceedings were had against John Merryman, the District Judge of Maryland, the commissioner appointed under the act of Congress—the District Attorney and the Marshal—all resided in the city of Baltimore, a few miles only from the home of the prisoner. Up to that time, there had never been the slightest resistance or obstruction to the process of any court or judicial officer of the United States in Maryland, except by the military authority. And if a military officer, or any other person, had reason to believe that the prisoner had committed any offence [sic] against the laws of the United States, it was his duty to give information of the fact, and the evidence to support it, to the District Attorney; and it would then have become the duty of that officer to bring the matter before the District Judge or Commissioner, and if there was sufficient legal evidence to justify his arrest, the Judge or Commissioner would have issued his warrant to the Marshal to arrest him; and upon the hearing of the party, would have held him to bail, or committed him for trial, according to the character of the offense as it appeared in the testimony, or would have discharged him immediately, if there was not sufficient evidence to support the accusation. There was no danger of any obstruction or resistance to the action of the civil authorities, and therefore no reason whatever for the interposition of the military. And yet, under these circumstances, a military officer stationed in Pennsylvania, without giving any information to the District Attorney, and without any application to the judicial authorities, assumes to himself the judicial power in the District of Maryland, undertakes to decide what constitutes the crime of treason or rebellion, what evidence (if, indeed he required any) is sufficient to support the accusation and justify the commitment, and commits the party, without having a hearing even before himself, to close custody in a strongly garrisoned fort, to be there held, it would seem, during the pleasure of those who committed him.

The Constitution provides, as I have before said, that "no person shall be deprived of life, liberty or property, without due process of law." It declares that "the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrant shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the person and things to be seized." It provides that the party accused, shall be entitled to a speedy trial, in a court of justice.

And these great and fundamental laws, which Congress itself could not suspend, have been disregarded and suspended, like the writ of habeas corpus, by a military order, supported by force of arms. Such is the case now before me, and I can only say that, if the authority which the Constitution has confided to the judiciary department and judiciary officers, may thus, upon any pretext, or under any circumstances, be usurped by the military power at its discretion, the people of the United States are no longer living under a government of laws, but every citizen holds life, liberty and property, at the will and pleasure of the army officer in whose military district he may happen to be found.

In such a case, my duty was too plain to be mistaken. I have exercised all the power which the Constitution and laws confer on me, but that power has been resisted by a force too strong for me to overcome. It is possible that the officer who has incurred this grave responsibility, may have misunderstood his instructions, and exceeded the authority intended to be given him. I shall, therefore, order all the proceedings in this case, with my opinion, to be filed and recorded in the Circuit Court of the United States for the District of Maryland, and direct the Clerk to transmit a copy, under seal, to the President of the United States. It will then remain for that high officer, in fulfilment [sic] of his constitutional obligation, to "take care that the laws be faithfully executed," to determine what measures he will take to cause the civil process of the United States to be respected and enforced.

R. B. TANEY,

Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

The War—Its Cause and Cure

May 03, 1861

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.