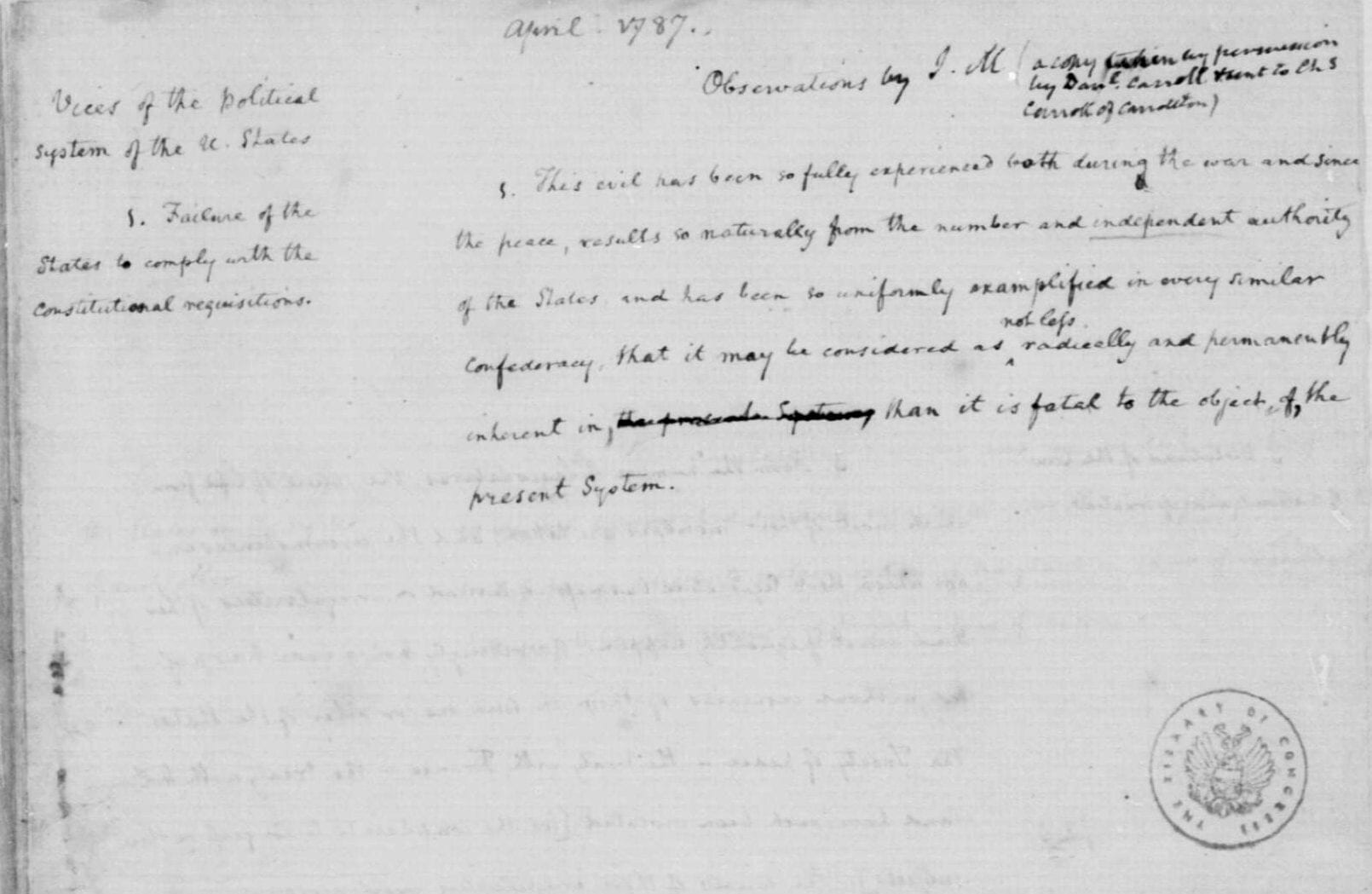

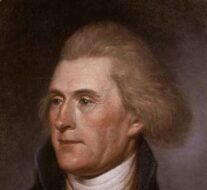

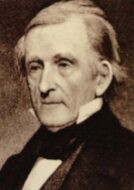

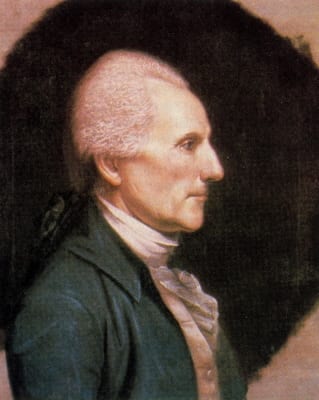

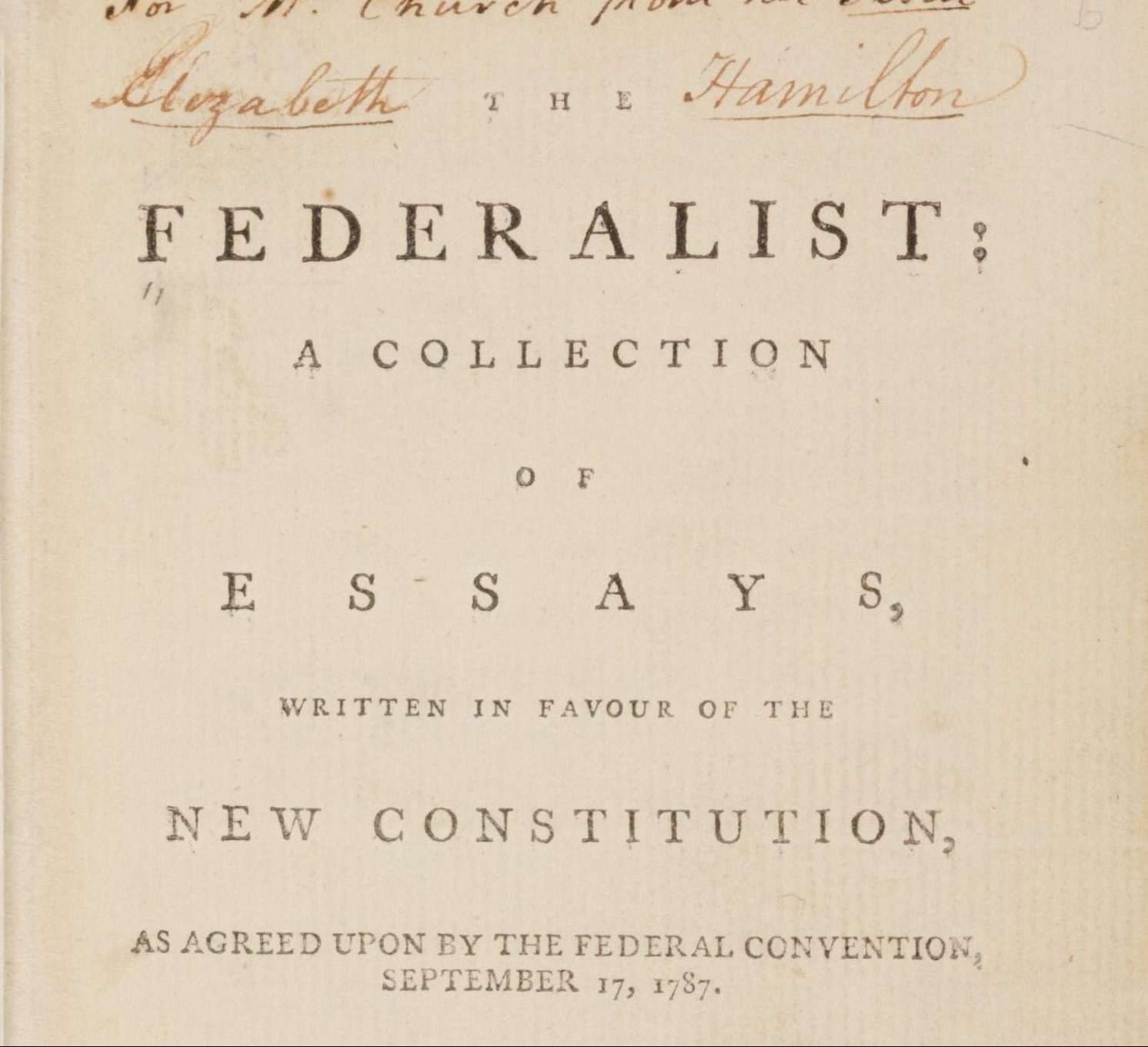

“From George Washington to James Madison, 31 March 1787,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/z0bj.

My dear Sir:

At the sametime that I acknowledge the receipt of your obliging favor of the 21st Ult. from New York, I promise to avail myself of your indulgence of writing only when it is convenient to me. If this should not occasion a relaxation on your part, I shall become very much your debtor—and possibly like others in similar circumstances (when the debt is burdensome) may feel a disposition to apply the spunge—or, what is nearly akin to it—pay you off in depreciated paper, which being a legal tender, or what is tantamount, being that or nothing, you cannot refuse. You will receive the nominal value, & that you know quiets the conscience, and makes all things easy—with the debtors.

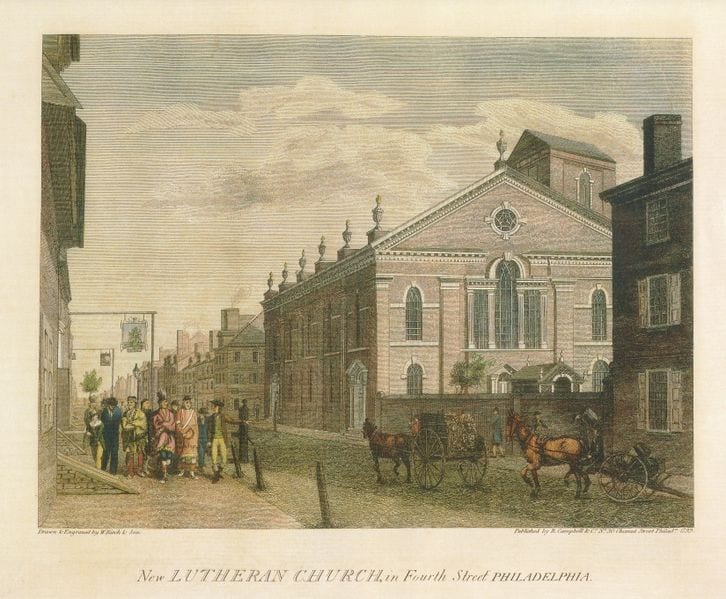

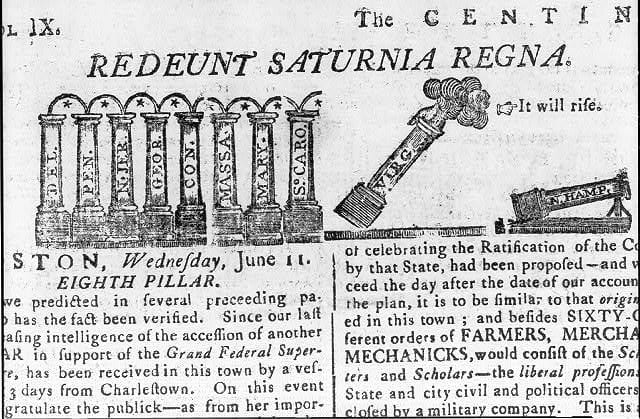

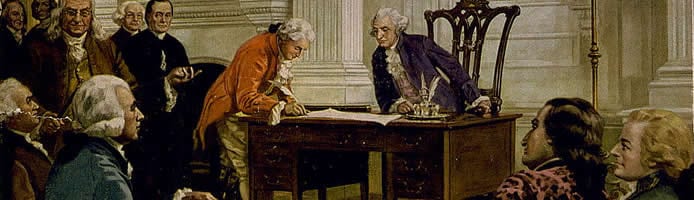

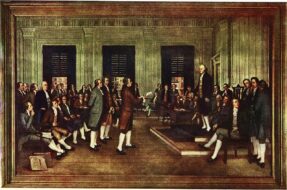

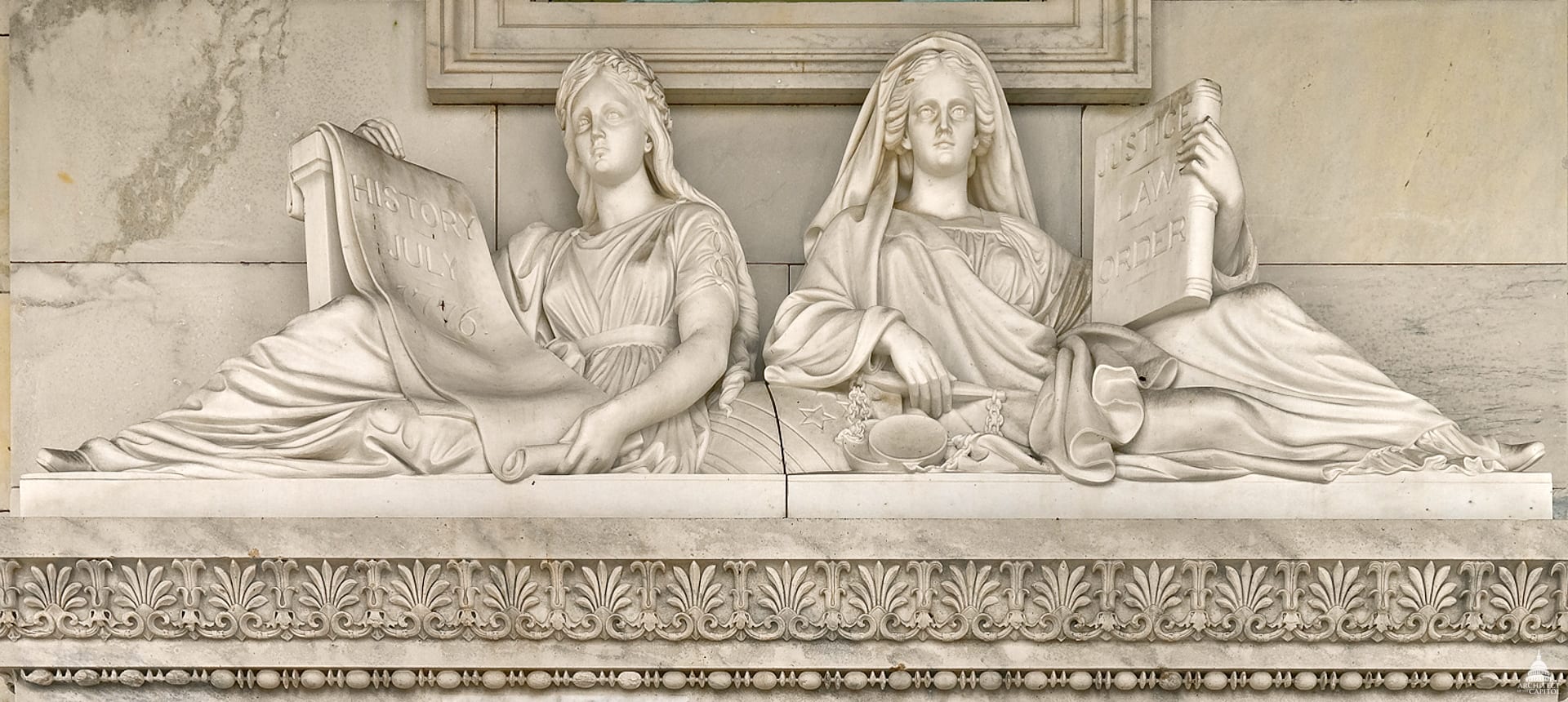

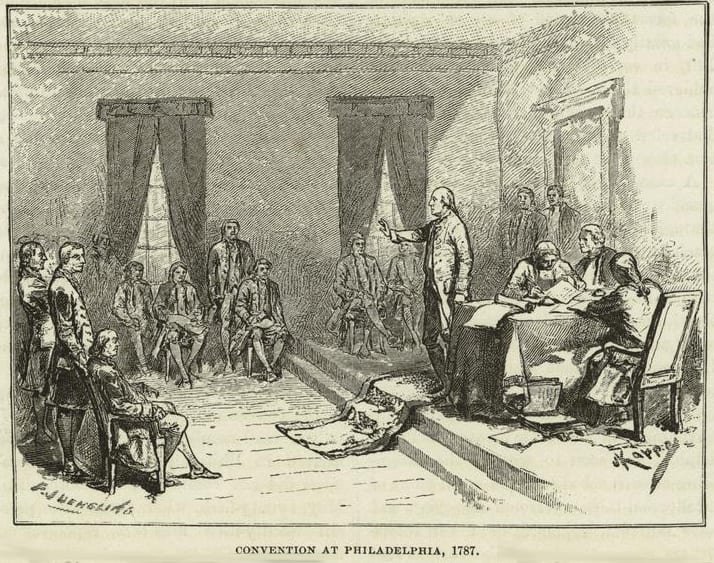

I am glad to find that Congress have recommended to the States to appear in the Convention proposed to be holden in Philadelphia in May. I think the reasons in favor, have the preponderancy of those against the measure. It is idle in my opinion to suppose that the Sovereign can be insensible of the inadequacy of the powers under which it acts—and that seeing, it should not recommend a revision of the Federal system, when it is considered by many as the only Constitutional mode by which the defects can be remedied. Had Congress proceeded to a delineation of the Powers, it might have sounded an Alarm; but as the case is, I do not think it will have that effect. . . .

I am fully of opinion that those who lean to a Monarchial government have either not consulted the public mind, or that they live in a region where the levelling principles in which they were bred, being entirely irradicated, is much more productive of Monarchical ideas than are to be found in the Southern States, where, from the habitual distinctions which have always existed among the people, one would have expected the first generation, and the most rapid growth of them. I also am clear, that even admitting the utility; nay necessity of the form—yet that the period is not arrived for adopting the change without shaking the Peace of this Country to its foundation.

That a thorough reform of the present system is indispensable, none who have capacities to judge will deny—and with hand and heart I hope the business will be essayed in a full Convention—After which, if more powers, and more decision is not found in the existing form—If it still wants energy and that secrecy and dispatch (either from the non-attendance, or the local views of its members) which is characteristick of good Government—And if it shall be found (the contrary of which however I have always been more afraid. of, than of the abuse of them) that Congress will upon all proper occasions exercise the powers with a firm and steady hand, instead of frittering them back to the Individual States where the members in place of viewing themselves in their national character, are too apt to be looking. I say after this essay is made if the system proves inefficient, conviction of the necessity of a change will be dissiminated among all classes of the People—Then, and not till then, in my opinion can it be attempted without involving all the evils of civil discord.

I confess however that my opinion of public virtue is so far changed that I have my doubts whether any system without the means of coercion in the Sovereign, will enforce obedience to the Ordinances of a General Government; without which, every thing else fails. Laws or Ordinances unobserved, or partially attended to, had better never have been made; because the first is a mere nihil— and the 2d is productive of much jealousy and discontent. But the kind of coercion you may ask?—This indeed will require thought; though the non-compliance of the States with the late requisition, is an evidence of the necessity.

It is somewhat singular that a State (New York) which used to be foremost in all federal measures, should now turn her face against them in almost every instance.

I fear the State of Massachusetts have exceeded the bounds of good policy in its disfranchisements—punishment is certainly due to the disturbers of a government, but the operations of this Act is too extensive. It embraces too much—and probably may give birth to new, instead of destroying the old leven.

Some Acts passed at the last Session of our Assembly respecting the trade of this Country, has given great, and general discontent to the Merchants of it. An application from the whole body of those at Norfolk has been made, I am told, to convene the assembly. . . .

It gives me pleasure to hear that there is a probability of a full representation of the States in Convention; but if the delegates come to it under fetters, the salutary ends proposed will in my opinion be greatly embarrassed and retarded, if not altogether defeated. I am anxious to know how this matter really is, as my wish is, that the Convention may adopt no temporizing expedient, but probe the defects of the Constitution to the bottom, and provide radical cures, whether they are agreed to or not—a conduct like this, will stamp wisdom and dignity on the proceedings, and be looked to as a luminary, which sooner or later will shed its influence. . . .

With sentiments of the sincerest friendship &c.

Go: Washington

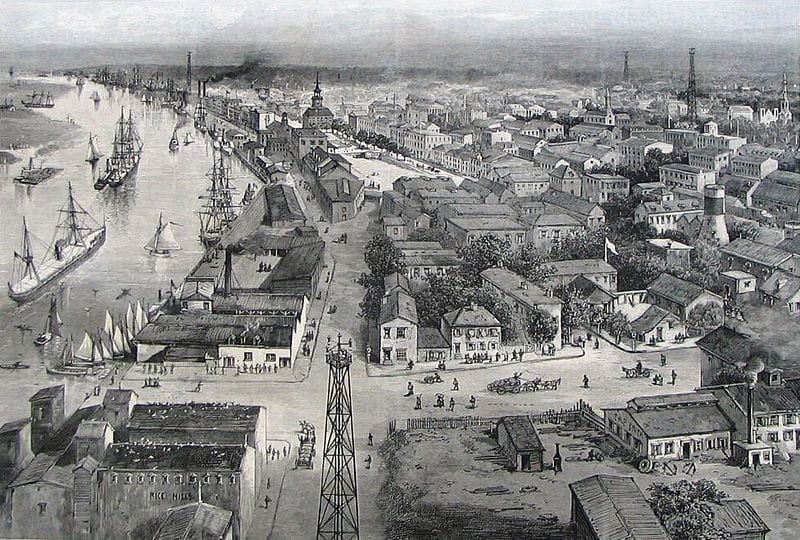

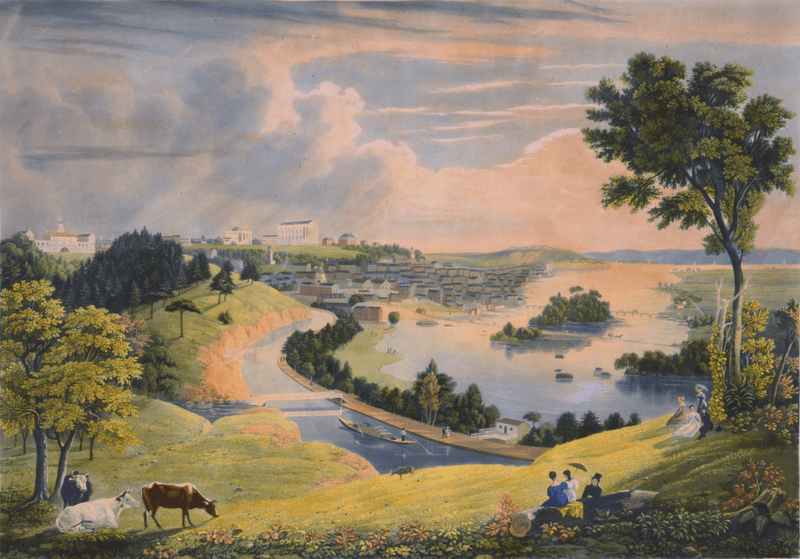

![Finley, A. (1829) Pennsylvania. Philada. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688548/.](/content/uploads/2024/02/Map-of-PA--273x190.jpg)