No related resources

Introduction

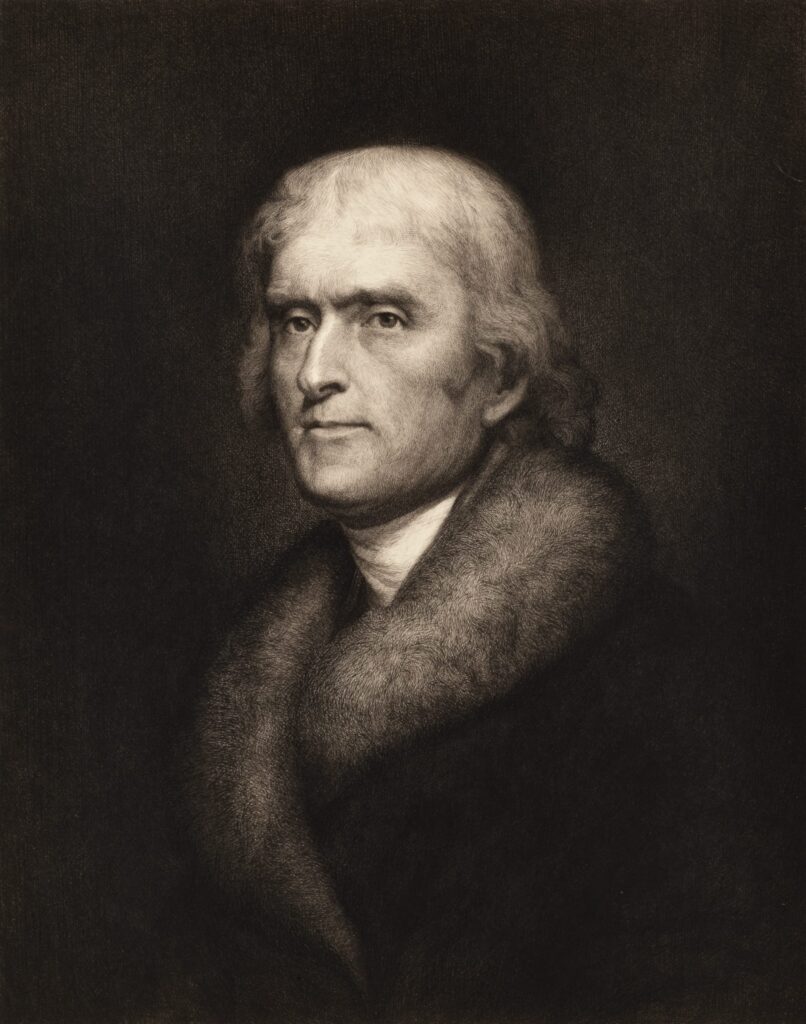

On a number of occasions during the first half century after ratification of the Constitution, members of Congress, the executive branch, and the federal judiciary considered the constitutionality of establishing a national bank. The initial occasion for debating the constitutionality of a national bank came in 1791 when Congress approved “An Act to Incorporate the Subscribers to the Bank of the United States” and sent it to President George Washington (1732–1799) for his signature. President Washington asked several members of his cabinet to offer their views on the act’s constitutionality. Attorney General Edmund Randolph (1753–1813) and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) prepared reports concluding that Congress lacked the power to create a national bank. Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton (1755/1757–1804), on the other hand, advised the president that this was a legitimate exercise of congressional authority. Siding with Hamilton, President Washington signed the bill.

In his “Opinion on the Constitutionality of the Bill for Establishing a National Bank,” Jefferson concluded that authority to establish a national bank could not be found in the powers specifically delegated to Congress and must be found in one of the more general grants of power, most likely in the clause empowering Congress “to make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers” (Article I, section 8, clause 18). Jefferson argued that the powers enumerated to Congress “can all be carried into execution without a bank”; therefore, establishing a bank was “not necessary, and consequently not authorized by this phrase.” Moreover, Jefferson added, although establishing a bank could make collecting taxes more convenient, “the Constitution allows only the means which are ‘necessary’ not those which are merely ‘convenient’ for effecting the enumerated powers.” Construing the necessary and proper clause in this fashion would “swallow up all the delegated powers.”

The debate about the constitutionality of a national bank is one of many occasions when members of Congress, presidents (President James Buchanan, Veto Message Regarding Land Grant Colleges, February 24, 1859, and Supreme Court justices (Justice Robert H. Jackson, Wickard v. Filburn, November 9,1942 and Chief Justice John Roberts, National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, June 28, 2012) considered the meaning and extent of the necessary and proper clause, which has served as a vehicle for expansion of federal power at various times in American history.

Source: “Opinion on the Constitutionality of the Bill for Establishing a National Bank, 15 February 1791,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-19-02-0051.

... I consider the foundation of the Constitution as laid on this ground that “all powers not delegated to the U.S. by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states or to the people” [XIIth Amendmt.].1 To take a single step beyond the boundaries thus specially drawn around the powers of Congress is to take possession of a boundless field of power, no longer susceptible of any definition.

The incorporation of a bank, and other powers assumed by this bill, have not, in my opinion, been delegated to the U.S. by the Constitution.

I. They are not among the powers specially enumerated, for these are

1. A power to lay taxes for the purpose of paying the debts of the U.S. But no debt is paid by this bill, nor any tax laid. Were it a bill to raise money, its origination in the Senate would condemn it by the Constitution.

2. “to borrow money.” But this bill neither borrows money, nor ensures the borrowing it. The proprietors of the bank will be just as free as any other money holders to lend or not to lend their money to the public. The operation proposed in the bill, first to lend them two millions, and then borrow them back again, cannot change the nature of the latter act, which will still be a payment, and not a loan, call it by what name you please.

3. “to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the states, and with the Indian tribes.” To erect a bank, and to regulate commerce, are very different acts. He who erects a bank creates a subject of commerce in its bills, so does he who makes a bushel of wheat, or digs a dollar out of the mines. Yet neither of these persons regulates commerce thereby. To erect a thing which may be bought and sold, is not to prescribe regulations for buying and selling. Besides, if this was an exercise of the power of regulating commerce, it would be void, as extending as much to the internal commerce of every state, as to its external. For the power given to Congress by the Constitution does not extend to the internal regulation of the commerce of a state (that is to say of the commerce between citizen and citizen) which remains exclusively with its own legislature; but to its external commerce only, that is to say, its commerce with another state, or with foreign nations or with the Indian tribes. Accordingly the bill does not propose the measure as a “regulation of trade,” but as “productive of considerable advantage to trade.”

Still less are these powers covered by any other of the special enumerations.

II. Nor are they within either of the general phrases, which are the two following:

1. “To lay taxes to provide for the general welfare of the U.S.” that is to say, “to lay taxes for the purpose of providing for the general welfare.” For the laying of taxes is the power and the general welfare the purpose for which the power is to be exercised. They are not to lay taxes ad libitum2 for any purpose they please; but only to pay the debts or provide for the welfare of the Union. In like manner they are not to do anything they please to provide for the general welfare, but only to lay taxes for that purpose. To consider the latter phrase, not as describing the purpose of the first, but as giving a distinct and independent power to do any act they please, which might be for the good of the Union, would render all the preceding and subsequent enumerations of power completely useless. It would reduce the whole instrument to a single phrase, that of instituting a Congress with power to do whatever would be for the good of the U.S. and as they would be the sole judges of the good or evil, it would be also a power to do whatever evil they pleased. It is an established rule of construction, where a phrase will bear either of two meanings, to give it that which will allow some meaning to the other parts of the instrument, and not that which would render all the others useless. Certainly no such universal power was meant to be given them. It was intended to lace them up straitly within the enumerated powers, and those without which, as means, these powers could not be carried into effect. It is known that the very power now proposed as a means was rejected as an end by the convention which formed the Constitution. A proposition was made to them to authorize Congress to open canals, and an amendatory one to empower them to incorporate. But the whole was rejected, and one of the reasons of rejection urged in debate was that then they would have a power to erect a bank, which would render the great cities, where there were prejudices and jealousies on that subject, adverse to the reception of the Constitution.

2. The second general phrase is “to make all laws necessary and proper for carrying into execution the enumerated powers.” But they can all be carried into execution without a bank. A bank therefore is not necessary, and consequently not authorized by this phrase.

It has been much urged that a bank will give great facility, or convenience in the collection of taxes. Suppose this were true: yet the Constitution allows only the means which are “necessary” not those which are merely “convenient” for effecting the enumerated powers. If such a latitude of construction be allowed to this phrase as to give any non-enumerated power, it will go to everyone, for there is not one which ingenuity may not torture into a convenience, in some way or other, to some one of so long a list of enumerated powers. It would swallow up all the delegated powers, and reduce the whole to one phrase as before observed. Therefore it was that the Constitution restrained them to the necessary means, that is to say, to those means without which the grant of the power would be nugatory.

But let us examine this convenience, and see what it is. The report on this subject, page 3, states the only general convenience to be the preventing the transportation and re-transportation of money between the states and the treasury. (For I pass over the increase of circulating medium ascribed to it as a merit, and which, according to my ideas of paper money is clearly a demerit.) Every state will have to pay a sum of tax-money into the treasury: and the treasury will have to pay, in every state, a part of the interest on the public debt, and salaries to the officers of government resident in that state. In most of the states there will still be a surplus of tax-money to come up to the seat of government for the officers residing there. The payments of interest and salary in each state may be made by treasury orders on the state collector. This will take up the greater part of the money he has collected in his state, and consequently prevent the great mass of it from being drawn out of the state. If there be a balance of commerce in favor of that state against the one in which the government resides, the surplus of taxes will be remitted by the bills of exchange drawn for that commercial balance. And so it must be if there was a bank. But if there be no balance of commerce, either direct or circuitous, all the banks in the world could not bring up the surplus of taxes but in the form of money. Treasury orders then and bills of exchange may prevent the displacement of the main mass of the money collected, without the aid of any bank: and where these fail, it cannot be prevented even with that aid.

Perhaps indeed bank bills may be a more convenient vehicle than treasury orders. But a little difference in the degree of convenience cannot constitute the necessity which the Constitution makes the ground for assuming any non-enumerated power.

Besides, the existing banks will without a doubt enter into arrangements for lending their agency: and the more favorable, as there will be a competition among them for it: whereas the bill delivers us up bound to the national bank, who are free to refuse all arrangement, but on their own terms, and the public not free, on such refusal, to employ any other bank. That of Philadelphia, I believe, now does this business by their post-notes, which by an arrangement with the treasury, are paid by any state collector to whom they are presented. This expedient alone suffices to prevent the existence of that necessity which may justify the assumption of a non-enumerated power as a means for carrying into effect an enumerated one. The thing may be done, and has been done, and well done without this assumption; therefore it does not stand on that degree of necessity which can honestly justify it.

It may be said that a bank whose bills would have a currency all over the states would be more convenient than one whose currency is limited to a single state. So it would be still more convenient that there should be a bank whose bills should have a currency all over the world. But it does not follow from this superior conveniency that there exists anywhere a power to establish such a bank; or that the world may not go on very well without it.

Can it be thought that the Constitution intended that for a shade or two of convenience, more or less, Congress should be authorized to break down the most ancient and fundamental laws of the several states, such as those against mortmain, the laws of alienage, the rules of descent, the acts of distribution, the laws of escheat and forfeiture, the laws of monopoly?3 Nothing but a necessity invincible by any other means can justify such a prostration of laws which constitute the pillars of our whole system of jurisprudence. Will Congress be too strait-laced to carry the Constitution into honest effect unless they may pass over the foundation-laws of the state governments for the slightest convenience to theirs?

The negative of the president4 is the shield provided by the Constitution to protect against the invasions of the legislature 1. the rights of the executive 2. of the judiciary 3. of the states and state legislatures. The present is the case of a right remaining exclusively with the states and is consequently one of those intended by the Constitution to be placed under his protection.

It must be added however, that unless the president’s mind on a view of everything which is urged for and against this bill, is tolerably clear that it is unauthorized by the Constitution, if the pro and the con hang so even as to balance his judgment, a just respect for the wisdom of the legislature would naturally decide the balance in favor of their opinion. It is chiefly for cases where they are clearly misled by error, ambition, or interest that the Constitution has placed a check in the negative of the president.

- 1. What became the Tenth Amendment was the twelfth of twelve proposed amendments that Congress in 1789 approved for submission to state legislatures for ratification. The first two amendments were not initially approved (the original First Amendment dealing with apportionment of the House was never approved, and the original Second Amendment dealing with congressional pay raises was not approved until 1992). The third through twelfth of the proposed amendments eventually became the First through Tenth Amendments. Because it was unclear for some time which of the original twelve proposed amendments would eventually be ratified, officials referred to each of the amendments by the number they were assigned by the First Congress. Therefore, what is understood today to be the Tenth Amendment was referred to as the Twelfth Amendment in some writings during this period.

- 2. As much or as often as necessary or desired.

- 3. For the most part, these terms refer to the disposition of property. Mortmain is the perpetual ownership of land; escheat concerns the circumstances in which the government may take control of property in the event that there are no heirs or beneficiaries; forfeiture concerns the government’s ability to seize the property of citizens; monopoly is the exclusive possession of a trade or supply of a commodity or service.

- 4. The president’s power to veto laws passed by Congress, Article I, section 7.

Consolidation

December 03, 1791

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

![Finley, A. (1829) Pennsylvania. Philada. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688548/.](/content/uploads/2024/02/Map-of-PA--273x190.jpg)